“It was all ‘father, oh father’,” Bob Geldof says, mimicking a pious female voice addressing a priest. Then in his own voice: “Fuck off, you’re not my father.”

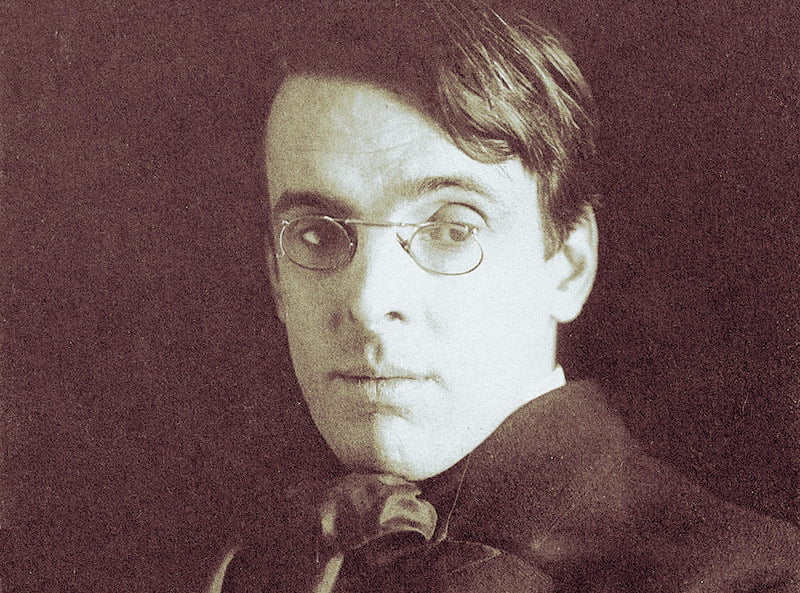

Geldof is railing against Irish groveling to the Roman Catholic church in Fanatic Heart, a documentary about the life and work of Ireland's great poet (and subject of my most recent novel): William Butler Yeats.

Geldof argues that the poet and literary statesman brought about revolutionary change in Ireland's struggle for independence, without firing a bullet. Instead of guns, his modus operandi was a poetic national vision, betrayed by the Roman Catholic nation-state that emerged after Irish independence.

So it was not until the election of Mary Robinson, 50 years after Yeats's death, that the country began to take the shape he had envisaged when he called it into being through poetry and myth in the 1890s and 1900s.

As an argument, it's not wrong, but as an attempt to explain Yeats's life and work, I found it one-dimensional and marred by Geldof's own prejudices.

Yeats, Geldof and 1916

For Geldof, the blood sacrifice of the 1916 leaders was plain wrong and Yeats's choice to birth a nation through cultural methods is vastly preferable. “It's easy to die,” he says. “I've been around this.” Making us think, as we are surely meant to, of the wife and daughter he lost to suicide.

It's much harder to live, he says. To live and work for a cause, day by slow and difficult day.

Perhaps. But it seems misplaced to compare his family's personal, private tragedy to the public, sacrificial martyrdom of the 1916 leaders. The motive, intent and outcome are completely different.

And to pull this point is to ignore that Yeats was a radical Republican, a member of the IRB (precursor to the IRA) and involved in revolutionary nationalism throughout the 1890s. His sustained interest was partly to impress the great love of his life, the fierce Republican Maud Gonne, but his interest pre-dated meeting her. It was ignited while he was still in his teens by meeting John O'Leary, the old revolutionary Fenian he immortalized in his 1913 poem, September 1913: “Romantic Ireland's dead and gone, it's with O'Leary in the grave.”

And, as Yeats admitted himself in a later poem, you can be indirectly guilty of violence without being the one to man the weapons:

I lie awake night after night.

And never get the answers right.

Did that play of mine send out

certain men the English shot?

The literal reply to Yeats’s question is almost certainly not. In “7, Middagh Street” Paul Muldoon captures the opposite question nicely : “If Yeats had saved his pencil-lead/would certain men have stayed in bed?”

Indeed, the play was not strictly his at all, having been largely written by his friend and collaborator, Lady Augusta Gregory. Maud Gonne always believed that it was this friendship that weakened Yeats's commitment to armed Republicanism and like her, most of the men of 1916 would have considered Yeats a turncoat. Or irrelevant

Ten years before he wrote “The Man and the Echo”, Yeats conducted an exchange of letters with Maud Gonne in which he said, “You are right – I think – in saying I was once a Republican … Today I have one settled conviction: create, draw a firm strong line, and hate nothing whatever. Not even, if he be your most cherished belief – Satan himself.”

Yet the question remained live for him until his death.

All that I have said and done,

Now that I am old and ill,

Turns into a question till

I lie awake night after night

And never get the answers right.

Fanatic Hearts

In contrast to Yeat's ambivalent questioning, Bob Geldof's documentary is full of certainty and answers. The title of the film, which he wrote as well as presented, is taken from a Yeats's poem “Remorse For Intemperate Speech” and decades ago, the young rock rebel took the “fanatic heart” lines as epigraph for his own autobiography:

Out of Ireland have we come.

Great hatred, little room,

Maimed us at the start.

I carry from my mother's womb

A fanatic heart.

In this film, we see that Geldof is still the punk rebel who hasn't come to terms with his anger against the theocratic Ireland in which he (and I) grew up.

There is much to admire in the documentary — and much omitted, which is understandable. Yeats was such a complex person, and such a wide-ranging writer, that no two-hour film could possibly capture it all. Geldof refers to him only as a poet, for example, but he also wrote 26 plays.

More significantly, the over-emphasis on the relationship with Ireland and Irish nationalism shortchanges the true heart of Yeats life and the importance of women, sex and love in his creative process.

Geldof reduces Yeats attraction to Iseult Gonne to a bad joke, and fails to figure her affect on his poetry, and the autobiography he was writing, at that time. He dismisses the women of Yeats's later years as “a gaggle”, displaying the blindness and poor-judgement that always accompanies such sexism. Women like Dorothy Wellesley, Ethel Mannin and Shackleton-Heald deserve better.

Ditto, Geldof's misreading of Maud Gonne's performance of the symbolic play, Caitlin ni Houlihan. And, indeed, his mockery of pious women.

All this anger, Geldof's own fanatic heart, keeps getting in the way of the film.

But a star-studded line-up of actors and performers reading favorite Yeats poetry provide a balance. Particularly fine readings are Liam Neeson, Bono (yes, I was surprised too!) and Ambassador Dan Mulhall. And everyone's favorite Yeats illustrator, Annie West, also makes an appearance.

To finish the film, Geldof tackles “Plato's ghost“. After all Yeats's successes, including the Nobel prize for literature; all the love affairs; the adoring younger wife; the two beautiful children; the many glorious friends; in short, all his ambitions met beyond his imaginings, Yeats was still seeking.

And, in the words of another great Irish anthem of spiritual doubt, still hadn't found what he was looking for. The poem makes this clear:

…I swerved in naught

something to perfection brought

but louder sang that ghost: “What then?”

Geldof answers Yeat's soul-searching question with one word: Ireland.

This is nonsense. A travesty, actually.

Yeats's great life quest was not for Ireland, but for love. He was no Freudian but it is easy for us, 100 years after Freud, to see how being denied love from his damaged and depressed and distant mother resulted in a craving for sex and magic and left him unable to enjoy true intimacy, with his wife, his many lovers or his children. (For more on how this affected his relationship with Maud Gonne, see my novel, Her Secret Rose).

Love carnal and spiritual were deeply entwined in his mind and he sought both through peak experiences, using sex and drugs, spiritual experimentation and poetry.

For the last decade of his life, as he sought love with a series of women, and had an operation to rejuvenate his sexual potency he separated himself from Irish, and increasingly all, politics.

This simple poem, written on the brink of the Second World War, can be taken as his last word on such matters.

Politics

How can I, that girl standing there,

My attention fix

On Roman or on Russian

Or on Spanish politics,

Yet here's a travelled man that knows

What he talks about,

And there's a politician

That has both read and thought,

And maybe what they say is true

Of war and war's alarms,

But O that I were young again

And held her in my arms.

The big misfire in this documentary is elevating the political over the personal. The give-and-take intimacy of everyday love — that ordinary love which is the most extraordinary of all — was never to be for Yeats. This was the true longing of the poet's fanatical, complex heart.

Out of this longing, Yeats created achingly beautiful poetry about Ireland and Irish politics, yes, but also about art, mythology, religion, folklore, history, poetic tradition and, more than anything else, his great subject.

Not Ireland but that which Ireland represented to him: the mythical, inspirational power of devoted female love.

Nationalist politics, pass by!

My Yeats-Gonne biographical novel, HER SECRET ROSE: * If you’d like to buy it in ebook or print, you can purchase it here if you are in the UK Amazon.co.uk direct link and here for Ireland, US or the rest of the world: Amazon.com direct link

Review The Book: * If you’ve read the book and enjoyed it, could you leave a short review (it need only be a sentence or two) on Amazon, saying why you liked it. * If you’d like a free copy in exchange for a review, just email me and I’ll add you to my reviewers list.

Share The Book: * If you’ve a friend who likes literary historical fiction, could you pass on my website links.

For the ebook or pod: https://ornaross.com/my-book/her-secret-rose-the-yeats-trilogy-i/

For the special edition: https://ornaross.com/my-books/novels/secret-rose-special-edition/

Thank you so much!

1 thought on “WB Yeats’s Fanatic Heart Was Not For Ireland But For Love”

Comments are closed.