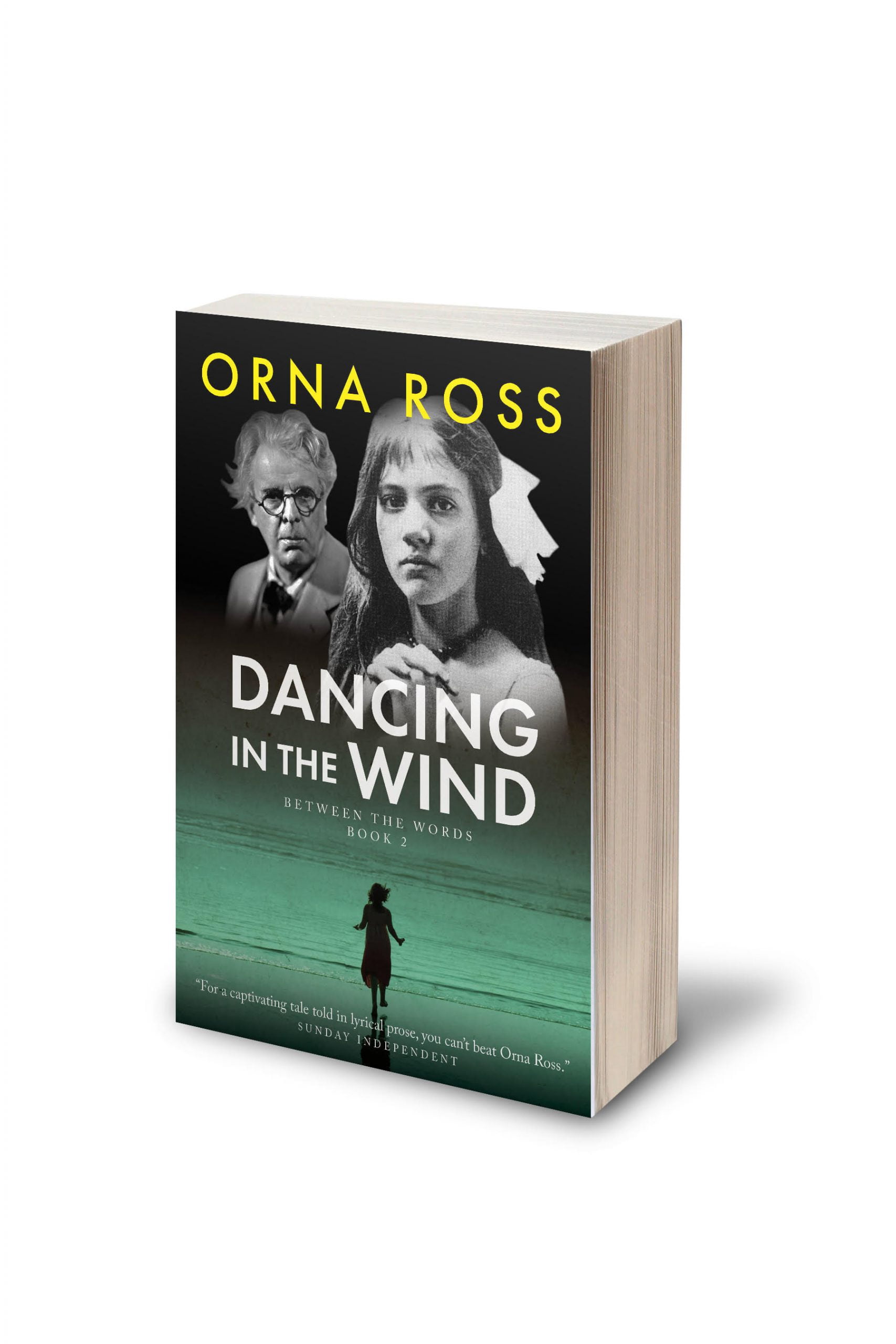

This is a snippet from my current work in progress, Dancing in the Wind. This section centers on the friendship between Iseult Gonne and the poet, editor and mentor, Ezra Pound.

CLICK THE “SIGN UP” BUTTON to become a fiction patron and help shape this work, by contributing your ideas about what might happen next. When the book is published, you'll be named in the credits and first to receive a copy. You'll also receive monthly extracts from the book to see your input into the story.

Until next time, happy reading!

Fiction Member Signupx Orna

Iseult and Ezra Pound walk by the river at St James Park. She is a picture of Parisian chic: wide-brimmed hat, well-cut day-dress, simple style worn with an elegance that draws the eye. That girl could have worn sackcloth and the eye would be drawn. It was the bearing as much as the looks. Her mother had it and she'd taken it without even knowing she had it.

And it was all the more striking on her as she had more of a softness about her than poor Maud. For hadn't Iseult been loved all her life? Her mother might deny her, claim her as cousin or neice instead of daughter, but she never left Iseult in any doubt that she was loved. She'd embarrass you, actually, with her ma belles and ma cheries, lavished on her, as if to make up for the rest.

So with Iseult you got those soft cheeks with a haughty chin, mischievous eyes with an elegant turn of the head and hands. For most men, it was an intoxicating mix and beside her is a man to appreciate such: Mr Ezra Pound, looking for all the world like her jester. Trousers lime-green, no less, and tucked into his stockings. A leather waistcoat more than a century old. And over it all, a short coat of many colours. He strides beside her, out of breath, hands waving like he's juggling the words he's spitting at her about Yeats. The Eagle, he calls him.

”…So he is calling on his ancestors, not just the Yeatses but the Butlers and Pollexfens… as determined to marry as a maid, only from astrological, not fiscal, imperative. Transiting Saturn conjuncting Mars in the seventh house of Venus twinning Neptune heading for Uranus, pardon my ad stareums“.

Iseult laughs, guiltily. “Poor Willie. But it is all for nothing. Moura is no more likely to say yes now. Less so, in fact. She is obsessed with getting to Ireland and fighting for freedom”.

“And at 50, your mother cannot produce the progenial goods”.

“I do not know this English word…. progenial?”

“Progeny. Childer. Birthium. Pregnanzzzzzzzzzzzy.”

“Ezra!”

“Let us be frank, my dear,” says Ezra. “Even the Eagle cannot be that ignorant of female biology. With your mother, he is going through some medieval motions of poetic chivalry. He thinks Ireland needs them to take up the work they used to do together, back in the '90s.”

“It's the Rising. It has infected them terribly.”

‘Did that play of mine send out certain men the English shot?' he asked me the other day.

“Maybe it did but Moura does not rate him as a revolutionary now.”

“From the sounds of it, she'll soon set him to right. Me advisums: when she shrugs him the heave-ho, don’t let him start burning tapers to you.”

“Ezra! Honestly, the things you say.”

“It will be just because you're a scion of the house of Gonne. Try me, insteadium”. He lunges, half in jest, to kiss her, clumsily misses as she dodges out of his way.

“Fie Sir! You are a married man.”.

“Alas, I fell in love with a picture that never came alive. Whereas me…” He makes claws of his fists, mock snuffles and paws at her. “I am wildlife in the flesh. Grrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr!”

“And I, Sir, am as confined as a virtuous young woman must be.”

“Ach, really?” He pulls back, acting a picture of excessive disappointment. “The rectitudinals? You didn't strike me as a prude, Miss.”

“It is with regret that I must decline your chivalrous and cultivated offer.”

And they both break into laughter, looking fully at each other, happy with their mutual measure.

“Then to writing, me supposums,” Ezra says with more mock regret.

“Yes Sir, as arranged.”

Emerging from the protection of the park by a side gate, she feels the silence that was upheld by its thick foliage, fall away. Late afternoon is falling on London now, the summer light starting to cool and fade, but the city takes no notice of the rhythm of the day. Its motor cars keep tooting, the army trucks grind on. Ahead of her and Ezra a trudge towards Westminster Bridge, in the middle of the uproar.

She always knew the relief she'd feel on leaving Paris, getting to Normandy, or anywhere in the country. That was the nicest thing her father had ever done for her, purchase the villa “Les Mouettes” at Colleville, so she and Moura could spend their summers on the coast. If she were there now, she'd be walking alone, able to feel the fading of the day. She had a sudden great longing for its freshness.

London was worse, even, than Paris, maybe because of the war. Frumpy English ladies tramping grimly through the queues. Bandaged men, nursing their injuries, and their bottles, in doorsteps. And the noise! Carriages and motor cars, the omnibuses and trams, the sharp jingle of the barrel organ on Westminster bridge as they pass. To add to the tumult, Big Ben begins to ring out 5 o'clock. Every hour, the musical lead up, then the count, boomed out. Peremptory. And other hour dead.

The echo of the great bell follows them inside as Ezra ushers her into a corner café, and leads her to its corner table, without looking right or left for permission. He offloads the condiments onto the window shelf, and spreads his papers across the white linen.

Her writing, marked with red lines and corrections.

“There is much here that is fine”, he tells her, a finger pointing to a particularly continuous red mark.

“I did warn you, Ezra,” she says. “But you would so insist.”

“Diddly-odlums, girl. I said ‘There is much here that is fine.'

A waitress comes to take their order. Iseult's stomach is cold with nerves. Food and drink are the last things wanted, but she orders an Assam tea and a sticky bun.

“Fine, as in more than acceptable, admirable in parts. ”

She looks down again at his markings, then up into his face. Kindness. That is almost worse than the corrections.

“My first advice is get rid of poetic diction, and all that is artificial or abstract”.

“Yes. Abstraction is my great fault.”

“You must breathe the fervor of your life into your work. Your own nature as it is, the evil with the good. Have you a pen? Good. Write this down. Read everything there is to read of the kind of work you want to do. Then find a few things out of the usual way which no other living person who matters has read.…”

He leans back in the chair, eyeing her through half-closed eyes, as if approximating her weight or heft.

“Read Voltaire’s Dictionnaire Philosophique or something of that nature in its entirety, then understanding all, drop all…”.

Crack!

He has leaned so far back that he has broken the leg of the chair.

“Ezra!” Iseult jumps up. What a sound. His back!

The talk stops. Everyone is looking around. Tea maids, all black dresses and white caps and aprons, are running to help.

Ezra is still talking.

“…but find some territory of print you can have all to yourself. Being French gives you an advantage here. It’s a great defence against fools…”

He is picking himself up only slowly, still talking, acting as if nothing at all had happened. His eyes twinkle at her, asking her in on the joke of it, the nonsense of it. Falling or sitting, what matter? “…Yes, a shield against fools and the half-educated, and the over-educated… dons of all sorts. You understand?”

The tea-drinkers return to their cake. Iseult sits back down, picks back up her pen.

“That is your shield. You understand?” He holds her gaze, suddenly solemn. The staff hover at a distance, still concerned, but his attention is all hers now. No joking now.

She looks fully again into his lynx-like eyes. They are the color of wood moss. “Yes Ezra, I understand. I must protect the part of me that writes from the critics and the commentators.”

”Good girl. Precisement! Then, if you give yourself over to me, you shall soon think yourself born in free verse”.