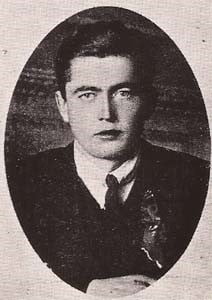

Con McCarthy: died Jan 10th 1923 in the Irish Civil War

Ninety-nine years ago, my great-uncle Con (my father's uncle, pictured left), was shot and killed in the Irish Civil War in Wexford. Fifty years later, I grew up in the same small rural village as him, a village called Murrintown, a village that never mentioned the war.

The Civil War, that is. There was no shortage of stories and monuments to the glories of other wards, especially our glorious 1916 Rising against British rule and our glorious War of Independence of 1918 to ’21, and our glorious admission into the League of

Nations in 1924.

But the Civil War of 1922/23? A blank page in the history books. And no mention of it at home either.

This short, bitter dispute drove a divide through Irish society that split male and female friendships, families, and marriages. The divisions lasted for decades, and the shame and blame associated with that time fed the secrecy and silence that used to be so endemic in Ireland.

And still flourishes in some quarters.

Remembering the Irish Civil War 1922-23: The Divide

Back when I was growing up there, the village of Murrintown was tiny: a handful of houses, a church, school, post office, a couple of shops, a pub. Small as it was, an unspoken divide separated its few families. As children, we knew who was one of ‘us’ and who was on the other side.

We carried the divide within us. We were born to it and we passed it on, all without knowing what or why.

As I grew into my teens, I began to wonder what and why.

When I first heard about my uncle's killing, I was full of curiosity. It was murder, the whispers went. The story had it that his best friend had killed him. Was that true? How could that possibly be?

Had the friend really been a ‘Free Stater’ who’d supported the (partial) independence treaty with Britain? Had he really shot him because he was what Staters called an ‘Irregular’, opposed to the treaty? Had Con and others in my family tried to destabilise the fledgling state over this?

Remembering the Irish Civil War 1922-23: Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael

Con's sister, my great-aunt Agnes, had survived him and lately come to live with us. She was passionately republican and passionately Fianna Fáil. Her proudest boast was that President De Valera, the famed Fianna Fáil leader, had once slept in our house. She had the bed moved to her room afterwards and had slept on it ever since.

From her I learned that the divide centered around whether a family voted for Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael, the two organizations have dominated party politics in the Republic of Ireland since the foundation of the state. Yet the more I learned about them, the more these two opponents looked the same.

Both patriarchal, both pietistically Roman Catholic, both right of centre. Both ignoring most of what I—a young, left-leaning, progressive woman—thought important.

Auntie Ag evaded most of my questions but she did show me two pictures.

One of her in uniform, holding up the badge that said she had been a member of Cumann na mBan, the women’s auxiliary unit that had also fought against the British. And after the peace talks, against the treaty. And one of her dead brother (the picture above).

Yes, he’d been shot in the Civil War, she confirmed.

“But why?” I asked, excited that I was going to learn at last.

“He died for Ireland.”

“But how? Why? Who shot him? How did it help Ireland?”

She returned the pictures, with a tragic air, into their yellowing envelope. Slowly and solemnly, she replaced them in her dressing-table drawer, turned the key, and turned back to me with a face that told me she had nothing more to say.

“Why?” I tried again. “I don't understand.”

Nothing but a slow, sorrowful shaking of the head.

Remembering the Irish Civil War 1922-23: Silence

I turned to my parents. How could this have happened? How could two men who'd been close friends growing up, comrades in the War of Independence of 1921, have become murderous enemies a year later? And what part had my Auntie Ag played in

it all?

Nobody knew anything, my father said. Least said, soonest mended, my mother said.

“Someday,” I told my friend who sat beside me in school, “I'm going to find out what happened and I'm going to write a book about it.”

Then I grew up, and rejected it all—the public, nationalist politics and the private family history. I left home, went to university, found life, love, feminism, my own family, and a different way of thinking about everything.

When you reject something, though, you're not indifferent—as I learned when, approaching middle-age, I set about fulfilling that long-ago vow to my friend, and beginning that long-promised book.

By then I’d been working as a features journalist for a decade, so I began to interview people who’d been alive in that time (Auntie Ag was long dead).

I turned to old County Wexford newspapers, old documents in libraries and archives, old books written by those who’d been part

of the conflicts of that time. I began to make notes but there were so many gaps, so many secrets, so much silence.

Somewhere along the line, research and memory gave way to imagination.

Remembering the Irish Civil War 1922-23: The Novels

I never did find out what really happened to my great-uncle but it ceased to matter. It turned out that I was writing a novel, the story of another family, the Devereux-Parles, similar-but-different to mine. And another progressive young woman, Jo Devereux, similar-but-different to me, tracing her history back through the similar-but-different events of her life and her family's life.

I never did find out what really happened to my great-uncle but it ceased to matter. It turned out that I was writing a novel, the story of another family, the Devereux-Parles, similar-but-different to mine. And another progressive young woman, Jo Devereux, similar-but-different to me, tracing her history back through the similar-but-different events of her life and her family's life.

Jo leaves Ireland in 1978, in high dudgeon with her family, vowing never to return but she does come back, for her mother's funeral in 1995, to unearth an astonishing family story of love and revenge. In the way of generational sagas, understanding the past allows her to reclaim her future.

Writing about her and her family across the generations did the same for me.

After the Rising, Before the Fall and the upcoming In the Hour between them cover the lives of five generations, across two continents in a story that's not just for Irish people but for anyone who’s ever been involved in any kind of intimate conflict.

And for anyone who has ever felt the struggle between the urge for freedom and the longing for belonging.

As I look back over the writing of this trilogy, I see now why it had to be a novel. Only fiction could recreate those people who were wiped out of the history books. And only the inventions of fiction could contain the truths of that time—and its ambivalent legacy.

Remembering the Irish Civil War 1922-23: The Commemorations

It's not surprising that pride in a newborn nation focussed its attention on the conflicts that won Ireland her partial independence. Or that so many were ashamed of what happened afterwards, in that kitchen conflict, when brothers and sisters, friends and relations, turned their guns on each other.

The Civil War was far more personal, far more frightening and far harder to explain.

Dubbed ‘The War of the Brothers' (though plenty of women like my Auntie Ag, Con's sister, took part too), this conflict is far more relevant to the Ireland of the 2020s than the Rising or Independence War — as Brexit politics energise the prospect of a united Ireland, as advances in women’s and LGBTQ+ rights teach us something about peaceful evolution, as the never-ending

movements of emigration and immigration show up our notions of nation.

I offer my story about the people of Mucknamore as my contribution to the multitude of voices, from within and outside Ireland that we need to hear.

It releases some of the secrets and lies that Ireland interred in its new, partitioned nation. But don’t expect it to “solve” everything, or to leave no loose ends. That isn’t how it happens after a rising.

More than any other commemoration over the past decade, facing into those troubled times of a hundred years ago, deciding what we choose to remember and highlight, will show Ireland what it’s made of today.

To receive award-winning fiction from me each month, become a fiction patron on Patreon (just £3 a month).

To receive award-winning fiction from me each month, become a fiction patron on Patreon (just £3 a month).