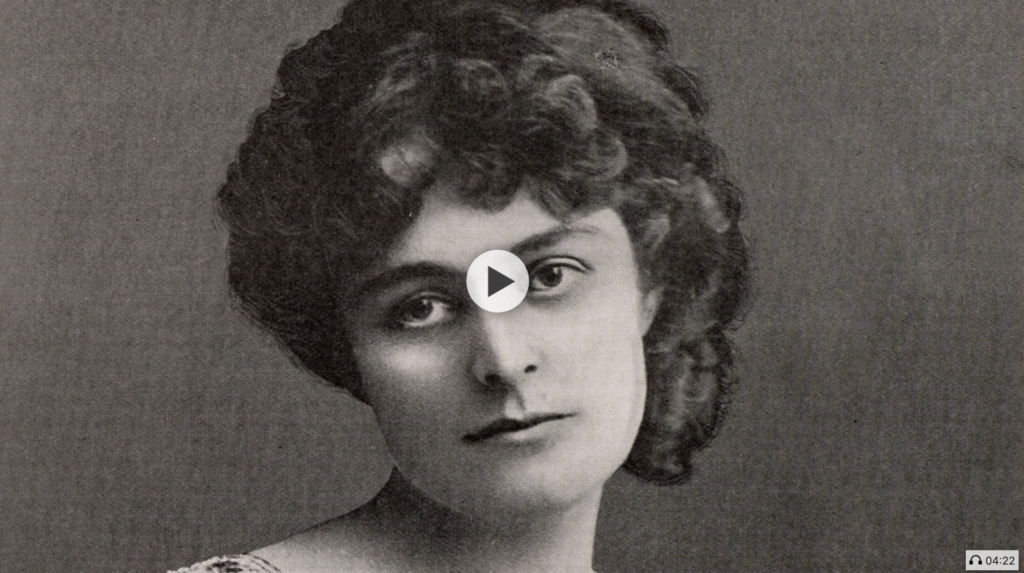

I tumbled across this great interview of Maud Gonne, with Dr Eileen Dixon, in which she talks about the land wars of the 1880s. From the RTE archive, it was recorded on 28 December 1945, and in it Maud Gonne MacBride describes witnessing evictions in her youth, and her consequent involvement in the Irish Land Wars.

She was 80 years old by then, rarely left her home and spent most of her time in bed but she still gives great stories about her early memories.

How, having spent eight years in France and Italy and Switzerland, she returned to Ireland as a Colonel's daughter and was very much enjoying the high life in Dublin attending balls and parties. She only became involved in the Land War when by accident she witnessed some evictions, and went from dancing with the evictors to fighting them.

“Then I didn’t want to go to balls and parties anymore for I would have had to dance and eat with the evictors…I couldn’t remain a mere spectator on such a one-sided battle.”

Enjoy this interview, from the RTÉ Archives Acetate Disc Collection which has been digitised with the support of the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (BAI) Archiving Scheme.

In her biography Gonne says of those times:

The great days of the Land League were when I was a child in France, when it was a real war with all the horrid savagery of war on both sides, when the evictor and his agent never knew from behind which hedge a bullet would come. The landlords, the British Garrison were on the run then as they were again in 1922.

When I saw those evictions in Donegal, the Land League had become a parliamentary and constitutional movement, with savagery admissible only on the side of law and order, and the landlords creeping back and everyone announcing crime and passing pious resolutions condemning murder while deprecating evictions.

Even the grabbers of evicted farms were becoming respectable; gradually the evictions were forgotten; John Redmond became England's great recruiting agent and appealed to the sons of those evicted tenants to join the English army and fight for home rule in Belgium…

Till Ireland is free her people cannot be free or prosperous. Only in spasmodic moments do the whole people seem to realise this. A minority of them always do and to this minority Ireland as a nation owes her existence.

Perhaps it is virtue, if only a negative one, that our race cherish the names and memories of some of that minority when they are dead, cherish them and honour them above those of the majority they have acclaimed in life, but whom they forget and scorn when they have passed away.

This passage was what first ignited my interest in seeing a statue to Gonne in Dublin. She was one of the minority that held to the tenet: Till Ireland is free her people cannot be free or prosperous.

We cherish her name and memory and all that she stood for then, and stands for now.