Her name? Her name is Generose, here is how her story flows:

through the latest news of war

our ruler coming out to say

‘Bombs Again!' Though his minions'

mincing words, force-feeding what

‘we' need to do, and why, (with regret)

some evil people (and some others)

must die;

through the soldiers jumping to,

while I, and my kind, are left gasping

behind, holding a small stand somewhere

like this, appealing to someone

like you.

So…

Can you come with me

to a place far from here, where

four or five m– No. Let

me begin again. Let me start

with myself, with yesterday when I

was clearing out my house,

‘and not before time' is what you

would say if you'd seen it. I was

making two piles – to hold or to go? –

when I found it. The book. Open,

face down, waiting for me to

return.

Shrugging away the me who thinks

she can think herself safe, I picked

it back up where I'd stopped,

and dropped, down again into that place

where four million people once died.

(Or was it five?) Yes, yes, genocide.

The woman's name is Generose, listen to how the story goes

When they'd hear the trucks of the killers

roll in, her people would grab the hands

of their children and flee to the trees.

At night they would lie facedown

on dead leaves, knuckling dirt through

their dreams.

One day she and her family were too slow

to go. The killers came into their house

with machete and gun, hacked

her husband to death then

made her climb up to lie down

on her own kitchen table,

in front of her daughter and son.

The soldiers were hungry, they said,

so they cut off her leg and sliced it

into six pieces and fried them up in

her pan.

It’s true. It’s all there in the book.

The mother's name was Generose, listen, listen, here's how it goes:

They ordered her children to eat

from the pan. The boy knew how to refuse

and was shot on the spot. The girl,

in terror, attempted to try. Can you imagine?

Can I?

It's the soldiers who get me each time,

the teaching it took to create them.

Where this happened is a place

made famous by kings who came

from afar to take what they would.

What one liked to take was the hands

of men he’d enslaved, the ones who had

failed to bring in their quota of crop. And chop

them off.

Crazed with the sight of the girl

in the corner forcing her mother

as meat through her mouth,

the soldiers overlooked Generose

as she crawled from the table

and out of her house. And so,

somehow, she survived. And so, she is told,

did her daughter and so she's

convinced that, somehow, she'll see her

again, and she lives and she

works, every which way for

that day.

So why have I told you all this? May I

reverse the question? May I ask

what you feel when you hear it? When you

see me stand here with my need to know

what was done to me too, what it's made

me do.

That’s why the poet wrote

her book though regurgitating

that leg made her sick for weeks

after. No? Outrageous, you say, to compare

I know what you mean, it's a question

of scale but the same choices call to

us all.

Kings will do what kings do. Soldiers

too. And if you don't want to know, I won’t

keep you. Let me back to the book

that knows what to own, what must be

let go.

Let me wait in the place I’ve come

to call home, with those who decline

to oppose, and hold to my hope

that the girl might be found,

and enfolded again (and their two dead men)

so we all might recall what we're taught

too well to forget: the long loving hold

of the strong waiting arms of a

mother.

Her name, her name is Generose and we all know how her story goes.

*

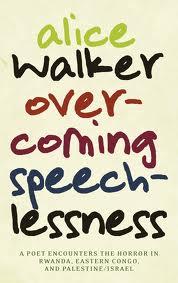

Inspired by Alice Walker and David Cameron.

You can read the extract from Walker's book Overcoming Speechlessness about Generose's experiences: here.