If you don't already know, my Yeats-Gonne book Her Secret Rose (first published in 2015) has morphed into a Yeats-Gonne series. There are both prequels and sequels to that novel now and it's had a major rewrite to fit this new scheme. I'll be talking about this rewrite with Joanna Penn on the ALLi podcast next week, if you're interested in hear more.

The first book in the series will be called A Life Before, and the second, The Holy Tree. I'm aiming to have these out in 2024, along with the revised version of Her Secret Rose. In this extract, the first paragraphs of the revised Her Secret Rose, Rosy Cross, the narrator, introduces herself.

To receive my quarterly fiction newsletter, What Happened When, and be first to read my award-winning novels, become a patron.

To receive my quarterly fiction newsletter, What Happened When, and be first to read my award-winning novels, become a patron.

Her Secret Rose: Chapter One: Introducing Rosy Cross

Here we go again. Another man fan of Mr WB Yeats has put out another book belittling Madame Maud Gonne. Full of the usual slurs and what have you, with extra imputations trumped up by himself. More than a hundred years since Madame began her work for Ireland and still the most jaundiced jackanapes give her a trouncing and get a hearing from those who should know better.

Enough now, me laddos! Reader, I’m turning to you. It's my hope that you’re one of the right-thinking women or men of this world? I don't mind whether you’re a woman like Maud Gonne, who wants to step into the manly parade, or one of those who chooses the womanly opposite. A man like WB, who craves and fears the female, or one who’s mastered the art of manliness. Or if you don't think of yourself as a man or woman at all. I care nothing for any of that. All I ask is that you’ll be open to truth.

Such beings are much needed now.

There was a time I thought the scholars had the answers but they're as lost as the warriors, God help them. Waving their footnotes in our faces, like that says their slant on things is gospel truth. Do they not know that even the gospels aren’t gospel?

None of us escapes our prejudices, me no more than anyone, and I’ll be making no claim such wise here but unlike the history buffs and literatis who’ve only lived what happened through the books, I was there. I lived in Paris and London in the last years of the old century, alongside Maud Gonne, and WB, and the other Irish in exile. And like them, I was part of the great flow back home, after the Easter Rising let up its roar for Irish independence.

At that time, only a small crew of us put ourselves out for Ireland, and we were all known to each other, by name at least. Maud Gonne and WB, being of the higher social order, knew me only a little, but I knew them a lot.

She went out of her way for me once, a doing I’ll never forget. She didn't need to and nobody but ourselves ever knew anything of it, until now.

Maud Gonne, a “woman who wanted to step into the manly parade.”

Between that day and this, I’ve read everything written about her and, of course, all that she wrote herself. Letters and memoirs, poems and plays, diaries and stories I've read—plus the praise and upbraidings of their admirers and detractors.

She and WB left a great trail for us, so they did, and I’ve followed it all the way in.

* * *

And who am I that you should trust me with the tale? You can call me Rosy Cross, a name I've had to adopt here to protect the living. “You can call me anything you like,” Nana used to say, “so long as you don’t call me too early in the morning.”

Nana was with me when, at the age of five, I stepped into the other thing you need to be informed about. The morning the knowing first came upon me. We were sitting outside the back of her house in Graignaspiddogue, watching the day go out and the stars come in.

As we sat in our dawdling silence, of a sudden she said, “Oh m'dear girl, it’s just been told to me. You're going to be given the knowing.”

I didn’t know what she meant. Next thing, the brightest star in the sky left the heavens and descended, coming down the bench we were sitting on, and circled three times around it. Around us.

One part of me was a small bit frightened but most of me felt wonder.

“Do you see it, Nana?” I whispered.

“I do, a grá,” she said out loud, very matter-of-fact.

Three circles complete, the star did a little dip, like a curtsy, before soaring away, back up to the heavens to return to its place among the others, so you couldn’t see it separate any more. As I looked for it, I felt all the stars up there turn into little beings, watching us now as much as we were watching them.

And then I felt myself to be one of them, that I too was a twinkling body of light. I had to get up and dance the shining that was myself, so I did. All the stars in the sky were joining in, and then too, so was Nana.

That was the first time I saw more than meets the eye and knew myself to be chosen. The knowing wasn’t always to be so joyous. In later years, I had many a time I wanted to renege on it, and view life straight up, like most people. Once you’ve known more, though, you can't choose to know less, and so it went. Things would be going along on the surface, then the second seeing would come into me.

I learned to manage it, first from my grandmother, and later from life itself. If I resisted, it would send me some hard woman lessons to knock me about until I'd submit and open up and admit it knows best. I learned how to go with what’s given. How to be a vessel. How to allow all.

That’s what fires this story, as much as any of my long reading and research. The feminal, Nana used to call it. Both Maud Gonne and WB went in search of her, but neither could let her lead. A more opinionated pair than those two would be hard to find–and nothing sees off the feminal like a strongly held opinion.

Agreeing about the great but differing about the small: that was always the way with those two. They couldn't even agree on when they first met. He always said it was 30th January 1889, when she came calling to his father’s house in London and immortalised the day in his memoir as beginning the troubling of his life. She said they met before that, in the house of their mutual mentor, John O’Leary, and had their first tête-a-tête on the walk home from Mr O’Leary’s house to her hotel, with WB carrying the books she'd been given.

He said, she said…

Here’s something you’d better hold in your head as you read this story: there were two Maud Gonnes and two WB Yeats. The living, breathing pair, what he called “the bundle of accident and incoherence that sits down to breakfast,” and the creatures they created to feed the newspapers, and stalk the history books. It took me a long time to know this.

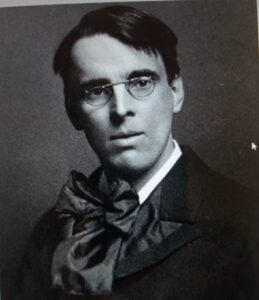

Every stitch, from the flowing tie to the black clerical cloak… chosen to announce himself as a poet.

They seemed so far above us, both of them. They were like gods to us. That was how they put themselves across, and that was how we took them up.

Their height alone was a wonder, especially hers. They lived when most of Ireland and England went half-hungry. If you didn’t see your ribs when you looked down at yourself naked, if you had a few decent rags to pull about your person, you were well got; if you’d two good meals a day and a winter coat, you were pure fortunate. Then along would come those two, striding the full length of their legs down Grafton Street or Piccadilly or the Champs-Élysées, Maud Gonne in her Parisian finery, with a hat atop her great height, one of those elevated concoctions they loved back then, with flowers and fruit. (Once I saw her wearing a bird’s nest, complete with stuffed canary.)

Her Great Dane would be stepping out in front, a slavering beast, tall as a donkey and as imperious as herself. And beside her would be some man, often WB, lost in his delight at being seen with her. Though all intense, stuck into whatever he was talking about, two hands fluttering like captured birds in front of his chest, still you could see it sitting on him: Look at me, walking down the highway with Miss Maud Gonne.

WB wasn’t rich the way she was rich, but he was an Irish Protestant, with the bearing of that class, and always costumed too. Every stitch, from the flowing tie to the black clerical cloak, from the eyeglass on a ribbon to the pointy black boots, chosen to announce himself as a poet.

Shure, you’d have to stop and stare. Even those who disdained them would be brought to stopping and staring.

Every word of all those magnificent lines he wrote about her beauty was true.

“…Pallas Athene in that straight back and arrogant head…”

…beauty like a tightened bow, a kind that is not natural in an age like this, being high and solitary and most stern…

…all full, as though with magnanimity of light…

…great-bodied and great-limbed, fashioned to be the mother of strong children…

…the beauty of lineaments which Blake calls the highest beauty because it changes least from youth to age…

Never listen to those who say she was anything less than that, they’re being pure political. And don’t mind those pictures that make her look like she was all chin and flinty stare. They don’t do her justice. Her beauty was borne by her presence and the feeling it gave you, as much as by her features, or bearing, or dress. It drew every man in the room, whether he was for the cause of Ireland, or against, and it drew us women too.

What she and WB did thrilled us, and sometimes threw us, for they could be both magnificent and foolish. When I went deep looking for them, to find the real people behind the thrillings and the throwings, they did not disappoint.

They were even more magnificent, and even more foolish, than our overheated talk about them.

Like most of what passed between them, his has become the accepted account, but in this book, we’ll be weighing male and female, outer and inner, public and private, in equal measure. When looked at from the woman’s side of the bed-sheet, most tales take a turning and this one more than most.

To receive my monthly fiction newsletter, What Happened When, and be first to read my award-winning novels, become a patron.

To receive my monthly fiction newsletter, What Happened When, and be first to read my award-winning novels, become a patron.