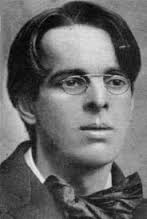

“I am what is called on the Internet a “superfan,” of WB Yeats and one of the things I most love and admire about this poet and teller of tales is the care he took with his books, not just in their writing —- he was an avid reviser and improver -—but in their design and presentation. And in how he represented his own ideas and intentions to potential readers through pro- motional efforts and reviews.

All this, by definition of The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), makes him an “indie author”: a writer who takes control, who acts as creative director of the entire book project, from concept to completion, through publication and beyond.

Back in 1890s, when WB Yeats was planning his book of talismanic short stories, he intended the sequence to finish with a triptych of visionary moments in a contemporary setting, held together by a single narrator.

These final three stories were to presage the end of the Christian era and the birth of a new order.

This mix of old and new, pagan and Christian, is the point towards which the other stories in the book have been aimed, but Yeats’s publisher, Arthur Henry Bullen, took fright at all this Celtic and Gaelic mysticism, telling the writer he was making himself too “heterodox.”

He insisted on the removal of the final two stories as a condition of publication, so the book ended with “Rosa Alchemica”, and the narrator pressing the rosary beads to his heart, instead.

By leaving the final two twists of the gyre out of The Secret Rose, the chronological and thematic structure the author so carefully constructed was broken and the meaning of his book eviscerated.

Bullen later privately published the two stories in a separate slim volume but it’s hard to imagine that was much consolation to Yeats.

We Have The Power

Fast forward to 2015, when new technology means authors no longer have to rely on publishers to reach readers. It is the 150th  anniversary of Yeats’s birth and I am completing the novel based on his life that I have been researching and writing for many years. I want to pay tribute to the master, the writer who has meant more to me, in so many ways, than any other.

anniversary of Yeats’s birth and I am completing the novel based on his life that I have been researching and writing for many years. I want to pay tribute to the master, the writer who has meant more to me, in so many ways, than any other.

A thought comes to mind: that I would love to put The Secret Rose stories back together again, the way Yeats originally intended them to be read and that I would most dearly love to put them into a book with my own novel, Her Secret Rose, so readers could understand what was going on in his life when he wrote those stories.

The latter idea gives me a real frisson. My book and Yeats’s book together, between two covers. The audacity!

But, hey, it’s 2015. I’m an indie author. Nobody can stop me as Bullen stopped Yeats. And what more fitting tribute could I make?

I am delighted to have had the tools and technology that allowed me to create this very special edition book.

But Which Version Is It?

WB Yeats was a determined reviser of all his work and his vision for The Secret Rose, where he had to unite so many different occult preoccupations and traditions, had him revising right up to a frenzy of last-minute proof corrections. And after publication, the rewriting went on.

The various versions of the stories are outlined in the much-admired variorum edition (1981), which follows the standard editorial convention of choosing the author’s last revised version as the definitive text.

I’ve taken a different approach. My intention is to be as true as possible to the artistic intentions of

the author, as he compiled that first edition of 1897.

At first I leaned towards reproducing the stories as originally written but then I read what Yeats said in 1925: “They were, as first published, written in that artificial, elaborate English so many of us played with in the ‘nineties, and I had come to hate them. I asked Lady Gregory’s help [and] we worked together … she now suggesting a new phrase or thought, and now I, till all had been put into that simple English she had learned from her Galway countrymen, and the thought had  come closer to the life of the people.”

come closer to the life of the people.”

I quite like the languorous, druggy, Pateresque prose of the 1890s and find it transports me to the otherworld more effectively than Lady Gregory’s “Kiltartanese” but I wasn’t going to issue the work in language Yeats had come to hate, so I used the Gregory-revised versions of the texts.

I restored the two stories axed by Bullen but also removed two of the weaker tales that Yeats later pulled, and substituted the later story, “Red Hanrahan,” for the 1890s version “The Book of the Great Dhoul and Hanrahan the Red”.

In short, I cut up different versions of the stories and put them all back together in the combination that I think would have put a smile on Yeats’s 33-year- old face, when he was still the troubled, controlling and confused genius depicted in the novel, who had not yet undergone the life-changing experiences with Maud Gonne that book revolves around.