Maud Gonne was a formidable activist and generous philanthropist, whose feminism and nationalism altered the course of Irish history, but she is still best known as the muse of the first Irish nobel laureate for literature, the great poet WB Yeats. This post is about some of the poems she inspired.

In the early part of his life, Yeats was a Romantic (capital R), heavily influenced by Rossetti, Shelley and other pre-Raphaelites and Romantics, in his ideas of what constituted a perfect love, and an ideal world.

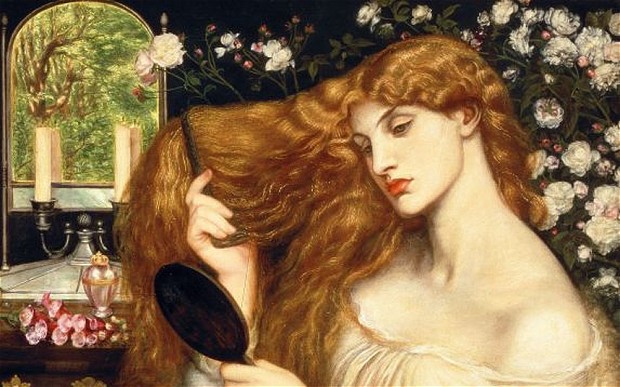

Rosetti Pre-Raphaelite woman, a trope that inspired Yeats's vision of Maud Gonne

In the courtly love tradition, a poet deliberately woos a muse as a career move: to extend his spiritual and creative capacities. The 16th century poet Dante set the model for this “suffering of desire” pursuit of the unattainable Beatrice and Yeats believed Dante's was “the chief imagination of Christendom”.

When Maud Gonne came calling to his father's London house in 1889, Yeats was already primed to cast a beautiful woman in this role, so he might become the “chief imagination” of his own time.

He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven

This poem was one of many written in the early 1890s, when Yeats knew little of Maud's real-life character or history.

The poem was originally entitled “Aedh Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven”. Yeats used a number of alter-egos in his poetry, to represent different dimensions of himself. Aedh embodies the pale, lovelorn man in thrall to la belle dame sans merci so beloved of the Romantics.

When the poems were collected in book form, “Aedh” was replaced with a more generic “He”.

He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven Had I the heavens' embroidered cloths, Enwrought with golden and silver light, The blue and the dim and the dark cloths Of night and light and the half light, I would spread the cloths under your feet: But I, being poor, have only my dreams; I have spread my dreams under your feet; Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

As “The Cloths of Heaven” makes clear, WB recognised that he was not Maud Gonne's equal and as a young poet, still living at home with his parents, as yet unknown and penniless, he had little to offer her, beyond his adherence to the cause of Ireland, which she so passionately believed in, and his secret, occult practices.

WB was in training as a mage as well as a poet and Maud Gonne, like most people in 1890s London and Paris, was fascinated by all the magic and supernatural traditions. This poem, his “wizard song” for her, draws heavily on those traditions and urges Gonne to choose the Tree of Life rather than the “broken branches” of bitter fighting.

The Two Trees Beloved, gaze in thine own heart, The holy tree is growing there; From joy the holy branches start, And all the trembling flowers they bear. The changing colours of its fruit Have dowered the stars with merry light; The surety of its hidden root Has planted quiet in the night; The shaking of its leafy head Has given the waves their melody, And made my lips and music wed, Murmuring a wizard song for thee. There the Loves a circle go, The flaming circle of our days, Gyring, spiring to and fro In those great ignorant leafy ways; Remembering all that shaken hair And how the wingèd sandals dart, Thine eyes grow full of tender care: Beloved, gaze in thine own heart. Gaze no more in the bitter glass The demons, with their subtle guile, Lift up before us when they pass, Or only gaze a little while; For there a fatal image grows That the stormy night receives, Roots half hidden under snows, Broken boughs and blackened leaves. For all things turn to barrenness In the dim glass the demons hold, The glass of outer weariness, Made when God slept in times of old. There, through the broken branches, go The ravens of unresting thought; Flying, crying, to and fro, Cruel claw and hungry throat, Or else they stand and sniff the wind, And shake their ragged wings; alas! Thy tender eyes grow all unkind: Gaze no more in the bitter glass.

A Poet to his Beloved by W.B. Yeats

Bring you with reverent hands

The books of my numberless dreams,

White woman that passion has worn

As the tide wears the dove-grey sands,

And with heart more old than the horn

That is brimmed from the pale fire of time:

White woman with numberless dreams,

I bring you my passionate rhyme.

Mongan Thinks of his Past Greatness

If Aedh, in Yeats's poetry, is the courtly lover, Mongan — based on the seventh century Irish prince, is the man of action, partnering Maud Gonne in their shared project of Irish nationalism.

An interesting 10th century story, Scél Mongáin, tells of the poet Forgoll, a poor student on whom Mongán takes pity and sends to the otherworld to bring back gold, silver and a precious stone. The student [who is far more like the real-life Yeats of this time than the powerful King] is granted the silver to keep for himself.

As with so many old Irish stories, the plot is not the point, existing only as a device that allows the bard to praise the magnificence of the other-world.

In the poem below, Yeats explores the ambivalence he always felt about the public and political life that so delighted Maud Gonne, and sets up the impossibility of a worldly man knowing that other-worldly magnificence, whether in the form of “the wind” or “the woman that he loves”, until — yes, you've guessed it — he dies.

Mongan Thinks of his Past Greatness I have drunk ale from the Country of the Young And weep because I know all things now: I have been a hazel tree and they hung The Pilot Star and the Crooked Plough Among my leaves in times out of mind: I became a rush that horses tread: I became a man, a hater of the wind, Knowing one, out of all things, alone, that his head Would not lie on the breast or his lips on the hair Of the woman that he loves, until he dies; Although the rushes and the fowl of the air Cry of his love with their pitiful cries.

He Wishes His Beloved Were Dead

Many of the poems in the voice of Aedh that Yeats wrote at this time use what was then a conventional trope of love-and-death.

Passion is unrequited to the degree that the lover retires, exhausted, ill, perhaps dying. There's also a tradition of passing the death wish onto the love object herself.

This is another sonnet in imitation of Ronsard, one of the most prolific sonneteers of the Renaissance. Yeats was modelling Ronsard to gain mastery of the sonnet form.

When Maud read this poem, apparently she laughed out loud. The reasons why have always intrigued me–in my novel, The Holy Tree, I attribute it to her understanding of WB's intense self-obsession. If she had to die so he could have “tender words”, then yes, he wished her dead. For me, this poem captures an aspect of their relationship that has been given very little attention by scholars. I find it very creepy and disturbing.

He Wishes His Beloved Were Dead Were you but lying cold and dead, And lights were paling out of the West, You would come hither, and bend your head, And I would lay my head on your breast; And you would murmur tender words, Forgiving me, because you were dead: Nor would you rise and hasten away, Though you have the will of the wild birds, But know your hair was bound and wound About the stars and moon and sun: O would, beloved, that you lay Under the dock-leaves in the ground, While lights were paling one by one.

When You Are Old

In this poem, a much more tender offering and much loved, Yeats addresses Maud directly, taking the focus off himself and his various alter egos (Aedh, Mongan, Michael Robartes), to focus on her and her spiritually questing”pilgrim soul”.

It's based on one of the sonnets another courtly lover, the Renaissance French poet, Pierre de Ronsard, wrote for his unattainable Helene. (You can see the original, which gave us the saying “gather your roses while they bloom”, here.)

By the time he wrote this, Yeats's love was cast in less in idealized mode and more in tune with the sorrows of Maud's life.

The poem reveals a knowledge of those sorrows and a desire to protect her.

When You Are Old When you are old and grey and full of sleep, And nodding by the fire, take down this book, And slowly read, and dream of the soft look Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep; How many loved your moments of glad grace, And loved your beauty with love false or true, But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you, And loved the sorrows of your changing face; And bending down beside the glowing bars, Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled And paced upon the mountains overhead And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

No Second Troy

No Second Troy Why should I blame her that she filled my days With misery, or that she would of late Have taught to ignorant men most violent ways, Or hurled the little streets upon the great, Had they but courage equal to desire? What could have made her peaceful with a mind That nobleness made simple as a fire, With beauty like a tightened bow, a kind That is not natural in an age like this, Being high and solitary and most stern? Why, what could she have done, being what she is? Was there another Troy for her to burn?

Broken Dreams

This poem was written when WB had begun to transfer his affections to Iseult, Maud Gonne's daughter.

Broken Dreams Broken Dreams There is grey in your hair. Young men no longer suddenly catch their breath When you are passing; But maybe some old gaffer mutters a blessing Because it was your prayer Recovered him upon the bed of death. For your sole sake—that all heart’s ache have known, And given to others all heart’s ache, From meagre girlhood’s putting on Burdensome beauty—for your sole sake Heaven has put away the stroke of her doom, So great her portion in that peace you make By merely walking in a room. Your beauty can but leave among us Vague memories, nothing but memories. A young man when the old men are done talking Will say to an old man, ‘Tell me of that lady The poet stubborn with his passion sang us When age might well have chilled his blood.’ Vague memories, nothing but memories, But in the grave all, all, shall be renewed. The certainty that I shall see that lady Leaning or standing or walking In the first loveliness of womanhood, And with the fervour of my youthful eyes, Has set me muttering like a fool. You are more beautiful than any one, And yet your body had a flaw: Your small hands were not beautiful, And I am afraid that you will run And paddle to the wrist In that mysterious, always brimming lake Where those that have obeyed the holy law Paddle and are perfect; leave unchanged The hands that I have kissed For old sake’s sake. The last stroke of midnight dies. All day in the one chair From dream to dream and rhyme to rhyme I have ranged In rambling talk with an image of air: Vague memories, nothing but memories.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Next Time: WB Yeats Poems Inspired By Iseult Gonne.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~