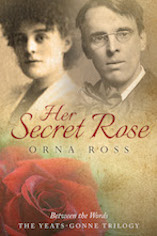

We’ll begin with the day WB immortalized in his memoirs, when she came calling to his house with her complexion like the blossom of apples, and her lineaments of the highest beauty, and her stature so great that she seemed to him to be of divine race. Maud always insisted they met long before, in Dublin at the house of their mutual mentor, the old Fenian, John O’Leary. They had become acquainted when he carried her books home, one afternoon, from Mr O’Leary’s house to her hotel, she said.

That fits her version of their relationship (faithful swain following her favour) rather than his (beautiful muse calling to his house, precipitating “the troubling” of his life).

Which brings me to the other thing you have to keep in your head at all times: that there were two Maud Gonnes and two WB Yeats: both the living, breathing man and woman, what he called “the bundle of accident and incoherence that sits down to breakfast” and the creations of each that they made between them, to feed the newspapers and stalk the history books.

His version of their meeting, like most everything that passed between them, has become the accepted account but in this book, we'll be weighing male and female, outer and inner, public and private, in equal measure. When looked at from the woman’s side of the bed-sheet, most tales take a turning. This one’s no different.

On their first meeting, we’ll let him have the word, as he wrote it all up so prettily. So it is January 30th 1889 and here comes Maud Gonne, buttoned and bonneted, banging the fine hall door of her uncle’s Belgravia home closed behind her, pulling on her gloves as she strides down the pathway, on her way to the famous visit.

She’s spent the morning gossiping with her sister and cousin, who are always thrilled when she arrives from France, bringing animal and bird friends and presents for all, and shaking up the English aunts and uncles with her lively generosity and rebellious spirit. So now she’s running late (as usual). Her letter of introduction to Mr Yeats said she would call at three, and it’s almost quarter-to already, and she doesn't realise that in her hurry, she's neglected to change out of her house slippers.

The cab at the kerb is a hansom, where the driver sits low in front, close to the horse, one of the new speedy ones, so she may yet be respectably on time. That is to say, fashionably, rather than rudely, late.

“Bedford Park, please,” she says as she gets in.

He flicks the reins and the horse begins its trot. “Right away, Mam.”

She picks up on the short “a”. “You are Irish?”

“Indeed and I am.”

“How very interesting. I have just returned from Ireland.”

“Have you now? And whereabouts did you find yourself while you were there?”

“Co Donegal. Falcarragh. Do you know it?”

“I don’t Mam. But I hear tell it’s beautiful in them parts.”

“It ought to be. Alas, there is much distress.”

Maud liked to talk to cabbies or servants or peasants, all those she called “The People”, believing them purer of heart than those of her own class. She leans forward now to share with him the full drama of what she saw in Donegal. The children clinging to their parents clothing, terrified of starvation or the workhouse that would keep them physically alive but at the cost of all other sustenance. A woman who threw herself screaming up on the back of one of the bailiffs sent to evict her.

“You’re a rare one, Mam, a lady like yourself to care a bit about the like,” the cabbie said.

“I care a great deal, Mr…?”

“O’Driscoll, Mam. The Tipperary O’Driscolls. If you’re ever in Borrisoleigh, you can enquire after the family. Just tell them Michael sent you and they’ll organize anything for you. Anything you need doing. Anything at all.”

He turned around and screwed up his face at her in what she guesses must be a smile.

The conversation lapses and Maud relaxes back. From Ebury Street, the journey takes them through the newly fashionable suburbs of Kensington, and then into the countryside and riverscapes around Hammersmith’s new station. Maud’s mind is on what is ahead. For a time now, since her father died and she met Lucien and made Ireland her interest, she has been collecting Irish connections.

Today, she seeks out this young poet who has recently issued not one but two books, both of which Mr O’Leary has said are most important, and one of which has affected her profoundly.

The first is a book of folklore, tales of old Ireland; the second, the one she can’t get out of her mind, is a volume of poems called The Wanderings of Oisin (a Gaelic name pronounced, she’s been told, as Usheen).

The folklore was fascinating and strange but the poems have lines so hauntingly beautiful and so redolent of the same old Ireland as the folklore. They have been circumambulating her mind behind her sleeping, and eating, and talking since she read them.

…And passing the Firbolgs’ burial-mounds,

Came to the cairn-heaped grassy hill

Where passionate Maeve is stony still;

And found on the dove-grey edge of the sea

A pearl-pale, high-born lady.

A pearl-pale, high-born lady, who… rode… something. How did it go again? She couldn’t quite remember now but there were lines she knew she would never forget.

…Her eyes were soft as dewdrops hanging

Upon the grass-blades’ bending tips

And like a sunset were her lips

A stormy sunset o’oer doomed ships…

She thinks he might have genius. Mr O’Leary believes so and had organized a letter of introduction from his sister, Ellen, to Mr John B Yeats, the father with whom the poet still lives. A portrait painter and, it is said, quite bohemian and full of Irish conviviality. There are four offspring, Willie and Lily and Lollie and Jack, and the poet is the eldest.

Everywhere, the Yeats family is spoken of as a slip of old Ireland in the branches of new London suburbs. And a light of artistic dedication among the murk. Willie and Lily and Lollie and Jack. Such names! She is keen to meet them but, yes, she is nervous. That’s why she’s been talking too much to the cabbie. Intellectuals always make her nervous, more than any other class of people.

She does hope they not anti-female, or inclined to think her a spy, that the O’Leary recommendation will carry her. She could never tell in advance who will be an ally. In Dublin, Mr Oldham, middle-aged and bluff, had seemed unpromising, but how he’d loved taking her to the Contemporary Club and throwing open the door and booming: “Maud Gonne wants to meet John O’Leary. I thought you’d all like to meet Maud Gonne.”

With this Irish family, she would do as she had done that day, when she’d felt so very shy. Mustering her courage, she’d said, “Mr O’Leary, I have heard so much about you. You are a leader of revolutionary Ireland and I want to work for Ireland. Can you show me how?”

With this Irish family, she would do as she had done that day, when she’d felt so very shy. Mustering her courage, she’d said, “Mr O’Leary, I have heard so much about you. You are a leader of revolutionary Ireland and I want to work for Ireland. Can you show me how?”

He’d liked this direct talk; the frown had vanished from his ancient, cagey eyes and he led her to a sofa, while Mr Oldham busied himself getting them a cup of tea.

“You must read,” he’d told her. “Read the history of our country, I will make you a list and lend you books.”

A citron color gloomed in her hair

But down to her feet white vesture flowed,

And with the glimmering crimson glowed…

Clip-clop, clip-clop of the horse’s hooves beat the rhythm of the beautiful, romance-soaked words.

…And it was bound with a pearl-pale shell

That waved like the summer streams,

As her soft bosom rose and fell…

Oh yes, these ancient whispers of Ireland show up the dullness of the grey expanse of London passing, on either side as the cab advances from narrow street to widening road on its journey to the outlying suburb.

London is no longer the city made famous by Dickens, where rich and poor, healthy and afflicted, used to co-mingle their public and private life on thronged and tiny streets. Now the center and the east side teem with the under-fed and under-clothed poor, while the middle-classes ride the expanding wave of the city out north and west, as new road upon new road of houses arrive in long strips along the river and the passenger railways.

Maud fancies if she were to take flight from the carriage and look down, she might actually see London ravenously advancing over the fields, like a concrete army, felling fields and hedges and trees, curling in around farms and villages and towns.

From such a vantage, she’d see among the rows of grey one cluster of houses up ahead, built in the warm, red stone that is now commonly called “London brick” but that was, in those times, much more uncommon. Its color offered late Victorians the same pleasure as the scarlet petticoat of an Irish colleen: all the more pleasurable for being unexpected. This red-brick cluster is Bedford Park, where the Yeats family lives.

Uncommon too is the way detail on each of the houses varies, so they avoid the regimental look of other middle-class suburbs. For Bedford Park is not inhabited, as most of the suburbs are, by bowler-hatted Mr Pooters, swinging their brollies towards the 8.15, who are content to be one of many but, in the main, by artists, writers and academics who prize individuality.

Maud’s hansom cab pulls up in front of No 3 Bleinham Road, the Yeats abode, and she lingers a moment to take a good look. The road is quiet, lined with trees; the house appears roomy, with Dutch gables, white casement windows and a porch with oriel windows and decorative tiles. (And, most important in the Yeats family’s decision to live here, though Maud does not yet know this: a cheap rent. Only £45 a year.)

“You can wait,” she says to O’Driscoll. “I shouldn’t be too long.”

She knows she will be at least an hour but she would keep the fare running for his sake, so Mrs O’Driscoll and the little O’Driscolls, of whom there is doubtless a surfeit, might have a good week of it.

His “Thank you a million times over, Mam” and his “Aren’t you awful good, awful good” follows her out of the carriage, through the little gate, and up the pathway but she has forgotten him, as she consciously pulls herself up, and steps with what she hopes is calm dignity towards the front door, for who knows who may be watching from those windows.

For a time Maud Gonne had thought she might be an actress, had taken some training to annoy her Uncle William and the other English aunts and uncles, and talked through many bedroom nights to Kathleen about becoming a famous actress-courtesan, consorting with the monarchs of Europe. She had meant it at the time. She was was so young then, and half-crazed in those days after dear Tommy had departed.

It was her Parisian friend, Lucien Millevoye, who had disabused her of this notion. “An actrice!” he’d snorted, in his French manner. “Pshaw! You underestimate your own power, my dear. An actrice, even one as great as Sarah Bernhardt, who is truly the greatest, even she only portrays the life of another. Where is the glory in that?”

She had agreed with him that day that she should make Ireland her country and now, on Ireland’s behalf, she draws on her acting training to make her entrance, to play at confidence. Suppressing a shiver, though it is not cold, not for January, she rings the doorbell of the Yeats abode, with a sense of significance.

It is as if her inner ear is already attuned to the sound of the bell tintinnabulating through the future, striking up the  poetry that is to come. And the spiritual and political work they will do together, it too will be a kind of poetry. What she and Willie Yeats are about to create together will alter the history of two nations and make them both famous, down through time.

poetry that is to come. And the spiritual and political work they will do together, it too will be a kind of poetry. What she and Willie Yeats are about to create together will alter the history of two nations and make them both famous, down through time.

Something in Maud already knows this; it is in hope of just such an outcome that she has come here today. So when the serving girl answers the door, she speaks to her slowly, with a sense of import. “I am Miss Gonne,” she says, proferring her calling-card and her letter of introduction from Ellen O’Leary. “Miss Maud Gonne, lately come from Ireland.”