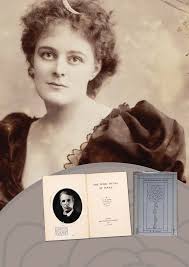

Like all young women of her class and time, Maud Gonne was raised to have a wide variety of accomplishments—singing, acting, writing, painting and more.

Her pictures have appeared widely and a short while ago, a rare piece of creative writing surfaced. “A Life's Sketch” was a contribution to a “Summer Sketch Book”, published by the weekly Freeman’s Journal on 15 July 1889.

The story gives a significant insight into her mindset at the time when she was first forging her relationship with WB Yeats. It's an autobiographical sketch in which the dying heroine reflects upon the signal passionate event of her life. Iseult (the name she was subsequently to give her daughter) is a young English gentlewoman in her dying days recalling an idyllic relationship with a soulmate, encountered, as she maintains, ‘too late’.

It wasn't time but courage that came between her and her happiness. She could have broken off her engagement to George, and consummated her affair with Langton.

What makes this story so fascinating is that Maud Gonne herself had not ‘neglected’ a similar opportunity. Maud, just like her heroine, was a young English gentlewoman, prone to illness, an orphan forced to live with a series of uncongenial relatives, falling in love in against the background of the romantic Auvergne, France with a hero who like Langton in her tale, is ‘a tall dark man’.

This is explored in some detail by Professor John Kelly, in this post. Kelly is better than most Yeats scholars at giving Maud Gonne her due but his sardonic tone reveals the suspicion and dislike that mar so much writing about her.

And there is always a tendency to take Yeats word as gospel. Kelly says:

In her affair with Millevoye Maud Gonne did take the safe, conventional route. She and Millevoye became lovers in Royat, and continued their relationship in Paris. By the time this story was published, she was embarked on a passionate love affair with this married man, delighted that it incorporated a political alliance that would give her life meanting.

By the time it was published, she was pregnant with her first child by him, her son Georges.

Maud Gonne's story deals with what Kelly calls the contrast between “natural unbiddable romantic passion … with the … falsities of social convention.” That is the real story of her own life—but with a different outcome.

From her perspective, what is most significant is not that she was a muse, or a fallen woman, or an unreliable memoirist. It is that she was a true romantic rebel, a heedless risk-taker in her emotional life, a masochist who longed for a dominating man to save her, but who was let down by them all.

All the men she cared most about—her father Colonel Thomas Gonne, the love of her life, the French politician Lucien Millevoye, her friend and erstwhile lover WB Yeats, her husband John MacBride, were philanderers or full-on sex pests, full of cant and hypocrisy.

Only Yeats was honest about his sexual proclivities. He explored them in his poetry, notably in the Crazy Jane sequence, with its declaration that “Love has pitched his mansion in / the place of excrement.”

But these were the men she loved, freely chosen, with an open heart. At the end of her life, the heroine in her story has real regrets. “To every one, I believe, the opportunity presents itself once, and if neglected never returns again; but we never profit by the experience of others. The price of that experience is often heavy, but cost what it may, we must buy it each one for himself.”

Unlike her, Maud Gonne had the courage of her convictions and the story provides a fascinating insight into her thoughts and feelings at a crucial moment of emotional and political and biological transformation for her.

The insights I've gleaned are being incorporated into my revised edition of Her Secret Rose. If you'd like to read this book as it emerges, I'm making it available to my fiction patrons in a monthly series of short novellas. Entry price is 2$ a month, find out more here

And now for Maud Gonne's story:

Yes, Nina, before I die, I would like to tell you the story of my life. You have often asked me, but I felt I could not tell even you, though you are always so good and patient with me. But now the approach of death seems to render everything easy.

Yes, Nina, before I die, I would like to tell you the story of my life. You have often asked me, but I felt I could not tell even you, though you are always so good and patient with me. But now the approach of death seems to render everything easy.

After all, there is not much to tell, Nina, darling. Remember, take care that you do not throw away your life’s happiness. To every one, I believe, the opportunity presents itself once, and if neglected never returns again; but we never profit by the experience of others. The price of that experience is often heavy, but cost what it may, we must buy it each one for himself.

My chance of happiness came to me here in this very place, just ten years ago, but it came too late. Now, you know why, when they told me I was dying, I insisted on coming here; it was not, as they thought, that I clung to the hope that the waters would cure me. God knows I do not want to live! But I longed to see once again the place where I had been happy.

But it is all changed since then; I hardly recognise the little mountain village, with its clear springs, which at that time but few doctors had found out, and which the fashionable world had never even heard of. It was so beautiful and peaceful then; now there are more hotels than cottages. There is the Casino, the theatre, the band, the usual noisy, chattering crowd; but the quiet restfulness of the place is gone.

Ten years ago I was very young, not seventeen, yet I was already engaged to George. Poor George! these years have changed him, too. It has not been all his fault, that from a gay, thoughtless boy he has grown into the hard materialist he is now; the society of a fretful invalid, like myself, must have been very trying; but, at least, he has consoled himself, and now, while I am dying, he is away in Norway fishing. There, see how unjust I am! He does not even know that I am very ill. I would not have him told; I wanted to have the last few days alone, at rest. His voice is so loud it jars me, and I could not bear to see him here.

You know, Nina, that I was an orphan, and was brought up by an aunt, who found me very much in the way, and was most anxious to get me married, so that I should not interfere with her own daughters, who were just coming out.

It was during my first London season that I met George. My aunt urged me to accept him. She did not hesitate even to tell me what a burden I was to her. I was anxious to escape from the dependent position I was in. I even persuaded myself I loved George. Poor fool! what did I know of love? What does any girl know of it?

Well, we were engaged, and life became a succession of balls, parties, and fêtes, for George was proud of me, and wished me to be seen everywhere. Our wedding was fixed for the summer, but I was always delicate, and long before the end of the season I became so ill that the doctor said I must leave London at once, and recommended the waters and the mountain air of Vernay. George had just received orders to return to his regiment, which at that time was stationed in Scotland, and my aunt could not leave her family, so it was decided that I was to go to Vernay alone under the care of my old nurse.

How well I remember the morning at the railway station. George, noisily fussy and anxious about me, sending porters in every direction to fetch me things I did not want; suddenly he rushed off, and after a few minutes returned, accompanied by a tall, dark man, whom he introduced to me as an old school friend, who by a lucky chance he had just caught sight of; he was starting for a sketching tour in the Auvergne, and at once promised to look after me on the journey, and see me comfortably settled at Vernay. “You will take care of her for me, Langton, won’t you?” said George, with an important air; he was such a child in those days, and I was his last new toy.

Ah, Nina, how shall I describe to you the weeks that followed. At first, I was so weak that I took but a languid interest in all that went on, only I knew that I was perfectly happy; happier than I had ever been before. Day by day I got stronger; Langton was always with me, he was so kind, so gentle. We used to sit for hours under the trees, here, where we are sitting now; only then it was a tangled little wood, instead of this trim garden, with its artificial rockeries and sham waterfalls. He used to read his favourite poems to me, with that musical voice of his. It was he who first taught me to care for literature. Or we would take long drives together through the yellow cornfields, or higher still where the road would wind among rugged cliffs and rocks thrown up in strange fantastic shapes by some old volcanic disturbance.

It was on one of these drives (I was almost well then, and could walk about again quite easily), we had left the carriage by the roadside, while we climbed a little higher to see the view. The scene was, indeed, wonderful; miles and miles of country stretched around us without a single habitation in sight. In the far east a faint haze hung over the Jura mountains; over the whole the cloudless blue of the sky and the glorious afternoon sunshine. A few sweet mountain flowers grew at our feet, a bird was singing in the air; involuntarily I turned, and found Langton’s eyes fixed on me with an expression I can never forget. In that one look our souls met, never again to be parted. With a little sob, I stretched out my hands to him; he held them tightly for a moment, his face was very pale, then he turned abruptly, and we went down the hill path together. All the way back to Vernay we never spoke, but as he helped me out of the carriage, “Goodbye, Iseulte”, he said, “goodbye: I must go tonight”.

*****

I have not seen him since. He went to India, and I married George. Last year I heard of his death. Now, darling, you understand why I am so happy to be dying, for I know that we shall meet. Death is less cruel than life! and I am so tired.