Eavan Boland Reading It's a Woman's World

I noticed while calendar rummaging this week that today, as well as being the birthday of one of my oldest friends (Happy Birthday Buts!), is the death anniversary of two of my favorite Irishwomen.

Both the activist Maud Gonne and the poet Eavan Boland died on April 27th, Gonne at her home in the Dublin suburb of Clonskeagh in 1953, passed aged 86; Boland at just 75, suddenly after a stroke during Covid-19 lockdown, in 2020.

If it wasn't for the coincidence of the anniversary, I probably would never have noticed quite how much Boland’s work illuminates and complicates themes that were central to Gonne's work, and vice versa.

In this post, I'd like to explore how both women circled around themes like womanhood and nationhood, family and belonging, history and myth, for their entire lives, in vastly different ways. And especially how they engaged, as women and in their work, with the construct of Mother Ireland.

Maud Gonne and Mother Ireland

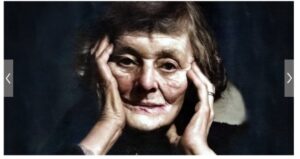

Maud Gonne in old age: a lifetime of political and social achievements

Maud Gonne passionately embraced the concept of Mother Ireland and drew on it as symbol and myth in her work. As a fervent nationalist and political activist, she saw Ireland as a feminised mother figure oppressed by masculine colonial forces, and she capitalized frequently on this symbol to rally support for Irish independence.

Maud Gonne's autobiography is entitled Servant of The Queen, causing much confusion. Her queen was not the Queen Victoria, who'd sat on the English throne for almost four decades of her life, or Queen Elizabeth, Sovereign of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and Head of the Commonwealth of her other Realms and Territories, who was not crowned until shortly after Gonne died. When she spoke of The Queen, she meant Cathleen ní Houlihan, the symbolic figure used to represent Ireland in literature and folklore.

This allegorical character, the personification of the Irish nation, appears most famously in the play “Cathleen ní Houlihan” written by William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory, and first performed in 1902 with Gonne in the starring role.

In the eponymous drama, Cathleen ní Houlihan appears at the door of as a poor old woman (the Sean-Bhean Bhocht in Irish) to tell a family of her suffering and the loss of her four green fields, the four provinces of Ireland, and try to persuade the young man of the house not to marry, but instead fight for Ireland. As the end of the play unfolds, as the young man does her bidding, the old woman transforms into a young woman “with the walk of a queen”, symbolizing the rebirth and renewal of Ireland that she promises will come from the family's sacrifice.

This vampiric character has been a potent symbol in Irish nationalist writing, used to evoke nationalism and encourage patriotic duty.

In addition to this dramatic personification of herself as her “queen”, on stage; Maud Gonne displayed a life-long devotion to being “one of the little stones on which the feet of the Queen have rested on her way to Freedom”. She consistently presented Ireland as pure, suffering, and put-upon, worthy of reverence and in need of rescue, in classic feminine mode.

In her speeches and public appearances, she often contrasted nationalist rhetoric about the enslaved good mother Ireland with the imperial, bad mother Queen Victoria of England, “the famine queen” who let Irish mothers and children starve.

For after all she is a woman…. and however vile and selfish and pitiless her soul may be, she must sometimes tremble as death approaches when she thinks of the countless Irish mothers who, sheltering under the cloudy Irish sky, watching their little ones starve, have cursed her before they died.…

Through her many collaborations with other activists, writers and orators, including the most famous of the many poets for whom she was a muse, her friend WB Yeats, Gonne not only embraced Mother Ireland, she embodied her, and she served her.

Eavan Boland and Mother Ireland

The poet Eavan Boland, on the other hand, critically examined the concept. In her essays and in her poetry, she challenged how such images and more generally “Irish poems simplified women [and] most [of all] at the point of intersection between womanhood and Irishness … the idea of the defeated nation’s being reborn as a triumphant woman… Dark Rosaleen. Cathleen ní Houlihan.”

And we might add, the Sean Bhean Bhocht, Hibernia, Banba, Fodhla and Ériu, (anglicised as Erin) and more. Like many countries, Ireland has a rich tradition of embodying the nation as a female figure, with several symbolic representations appearing in its literature, folklore, and political discourse, all feeding a notion of the nation as woman and the woman as national muse.

These idealized, unthinking representations of women intertwined with another symbolic representation of purity and self-sacrifice, the Virgin Mary, and were used by a patriarchal nation to impose very real constrictions on actual Irishwomen's lives and identities,.

Living, breathing Irish women were constantly placed outside the terms of reference of poetry and politics, except as symbolic mothers. Boland felt this stricture keenly. Becoming a woman poet (and by inference a female anything) in a culture that symbolises you out of existence is enormously challenging.

“The ordinary routine day that many women live–must live–to take just one instance, does not figure largely in poetry. Nor the feelings that go with it.” In many of her own poems Boland recovers details of domestic life that are absent from the literary renderings of female Irish roles in her youth: gardening, sewing, letter writing, calling the children in from play, everyday tenderness and chores. And the complexity of emotions and experiences that underwrite all this.

In her poem “Mother Ireland” she writes of the words she found as “seeds, raindrops”, and of how

From one of them

I learned my name.

I rose up. I remembered it.

Now I could tell my story.

It was different

from the story told about me."

Her approach was to demystify and reclaim the symbols and myths that define and restrict women's lives, by writing of how it actually felt to be herself, a woman, a writer, a mother, a resident of Dublin suburbia trying to reimagine what has been forever lost, what cannot be reclaimed because occluded by symbology and myth.

In this reimagining, and in her gender politics, she changed the scope and reach of Irish literature, immeasurably.

Eavan Boland's Mother and Maud Gonne

Side note: In my travels around these two women's lives this week, I found also a little story that connected their real lives… loosely. Maud Gonne had less than ten years to live when Eavan Boland was born. Boland's mother, the painter Frances Kelly, bridged the generations between them.

Apparently Kelly once sought a painting commission from Maud Gonne and was invited to visit Roebuck House, Gonne's home in Dublin. While there, she noted the famous collection of caged birds and queried how Gonne, the fervent advocate for national freedom, could reconcile the irony of her strong libertarian principles with the act of keeping birds confined in cages.

According to Jody Allen Randolph, Eavan Boland's biographer, she received neither an answer nor a commission.

Two Women, Two Feminisms

The difference between Maud Gonne and Eavan Boland in relation to Mother Ireland and nationalist symbology, was a difference of character, as much as anything.

Gonne had little time for analysis. She was a doer, whose forceful and activist personality drove her to adopt a glorifying view that aligned with her revolutionary ideals and her famously single-minded determination to defeat the British forces in Ireland.

Boland was a thinker, whose introspective and questioning nature led her to critique and redefine the symbol, focusing on the nuanced and often problematic aspects of such idealizations, after the foundation of the partitioned Irish state.

But the difference also relates to types of feminism and each represents an ongoing argument in women's studies.

When Boland writes in her poem, “It's a Woman's World”:

...our windows moth our children to the flame of hearth not history,

she's not writing of a woman like Maud Gonne, who definitely flamed the flame of history for her children, as for all others. She involved her apolitical daughter (most known as her niece or cousin in conservative Ireland) the Irish Civil War, and not only earmarked the role of “King of Ireland” for her son, Seán. She brought him into the Republican cause as a youth, supported his formation of an alternative political party in later life, and he has spoken of her influence in his co-founding of Amnesty International.

Gonne's feminism was equality feminism–assertive, public, and directly engaged, calling on change that allowed women the same rights and opportunities as men, particularly in the spheres of voting and national independence. Gonne's work with the Daughters of Ireland (Inghinidhe na hÉireann), and The Mothers which she founded, aimed at mobilizing women for the national cause, but also emphasized the importance of women's roles in public and political life, advocating for equal participation in the struggle for Irish freedom.

Boland's focussed on the undervalued aspects of women's lives, and interrogates the narratives, myths, and historical roles that have been imposed on women, aiming to reclaim and redefine women's roles.

Different, they undoubtedly were but as two highly committed, feminist Irishwomen, what unites them is greater than what divides them. Both women shared a deep engagement with, and commitment to Ireland, its history, and its cultural identity, grounded in gender.

Although their methods and focuses differed, each was an impassioned and influential activist who challenged the societal and cultural norms of their times and sought to redefine or question established narratives.

Both were political and poetical, to varying degrees, and each used her unique voice to explore, express and address enduring gender questions from her own generational and ideological perspective. In doing so, they both greatly expanded what was possible for all Irish women, at home and abroad. We have much reason to admire, and be grateful, to them both.