In a few hours time, I'll launch Secret Rose, my special edition two-in-one book tribute to WB Yeats.

I'll write soon about how it went and what I said… (I never know all in advance, so much depends on the group and the energy in the room).

What I do know:

- I'll be talking about the dream of writing this book, where it came from, what it took to do it… and why (the subject of another post soon).

- I'll sign each book with: “It takes a great reader to make a great book. Thank you for reading.” Yeats is easy to read in some places, sometimes more challenging, and possibly at his most challenging in this collection of stories. I'll publish a reading-guide to the book on this blog in a few weeks, when life has quietened again, but I will mention at the launch what I say in the introduction: that the stories are best read as prose poems, letting the words and ideas sink into bone and blood, rather than trying to understand them with the brain.

- I know I'll say something about putting my own novel between the same two covers as WB Yeats's book as an act of creative courage and talk about this great writer as an “indie author”. Yeats took an interest in his books from conception to publication adn promotion. That makes him indie, as defined by the Alliance of Independent Authors.

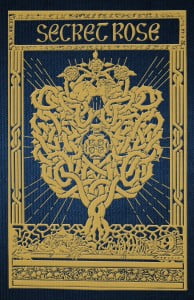

- I'll draw attention to the mystical symbology on the covers.

- I'll be offering a go raibh míle maith agaibh (Irish: a thousand thanks) to the following people:

- My family especially my Lynch sisters-in-law, who always turn out to support me every time. The launch will be dedicated to our sister Anne who died earlier this year of MND.

- My friends, online and offline, especially those who supported the crowdfunder campaign that enabled this book to be. Six of them have travelled to be at the launch in person and will receive their copy of the book there: Kathy Dillon, my old WoW partner; Maura Dolan and Deirdre Hassett, two of my schoolfriends; Catherine MacKerchar and Phil Mason, sister writers and long time supporters and Joni Rodgers, who's travelled all the way from Houston, Texas to be here.

- Said Joni, who as well as being a New York Times bestseller also edited the book, deserves special thanks. She is one half of the editorial duo that worked this book with me and the other half is her daughter, Jerusha. Joni’s unique blend of sharp intelligence and kind encouragement, and Jerusha’s keen eye and fast turnaround, were godsends to me during a very tight deadline.

- Designer Jane Dixon-Smith, who has worked with me since I started self-publishing and who designed both cover and interior of this special edition. Jane helped me go way beyond mere reproduction into capturing the spirit of the 1897 original. Jane, you are a wonder, always, but never more than on this project.

- Rebecca Souster from Clay’s, my printer, who also went to that place beyond the call of duty where excellence abides.

- Yen Ooi, Jay Artale, Valerie Shanley and Grainne Blair their help in getting the word out.

- Deirdre Hassett and Danny O’Sullivan for exceptionally generous support and encouragement.

- The library staff at The British Library and the National Library of Ireland.

- The Yeatsian academics, scholars and researchers whose work is the scaffolding without which this book could not have been built, most especially Damien Brennan, immediate past president of The Yeats Society and Professor Warick Gould, for reviewing the book in Yeats Annual.

- And, as always, Philip for opening the space and to Ornagh and Ross for cheering me on.

I'll read the two passages below from the books. And I'll draw attention to the dedication: “For all the writers everywhere. Dare.” Putting my book and WB Yeats's book together between two covers was an act of daring for me. Brass nerve, some would say, but I prefer to think of it as creative courage.

More soon!

FROM HER SECRET ROSE:

Olivia invites Cousin Lionel round. This passion WB has for Maud Gonne—what does he know of it? It is arid, Lionel believes; the lady’s not for turning. Maud Gonne’s kind of hero is the man of action. But if she, his dear cousin, is determined to set sail on an affair with Yeats, she needs to know that his friend has come to almost thirty years without yet putting out to sea.

Olivia is charmed, not deflected, by this knowledge, and next time she meets her intended, on a day out to Kent, she makes her declaration. They have both been so unhappy. Her marriage is a sham, and so often she has taken refuge in attractions to other men who were not right for her. WB’s love affair seems equally doomed. Are they not entitled to such happiness as they can create, together?

He does not seem enthused. Her cure for marital unhappiness is flawed, he believes. Knowing her as he does, he believes it the sort of flaw that arises from fineness, the sort she shares with her cousin. It comes from having a soul so distinguished and contemplative that the common world seems empty, and so they choose the extremes: sanctity or dissipation.

In Johnson’s case the Catholic Church. In hers… There he flounders, perhaps realizing how offensive he is being.

She says: He has it wrong, entirely. She is dismayed that he should have such thoughts of her. She has never voyaged with another, except in her imagination. He would be her first lover.

He (blushing) says: He is happy to know it.

She says: She is so happy to know him, to have met him. Had any other man said what he has just said… But she knows it comes from a discriminating soul.

He says: This is all to the good. But what of their various difficulties: her husband, his lack of money, the scandal, her daughter Dorothy? Is it correct that for having an affair, her husband can immediately divorce her and will gain unquestioned custody of the child?

She says: They must make sure they are not found out. Though her husband would have grounds to sue them, and destroy both their reputations, and keep her from Dorothy, she does not believe he would do so. He has a strong dislike of public scenes.

He says: They should not be hasty. Next time they meet, perhaps they might take an outing and discuss the question some more? Leaving, he gives her a platonic kiss on the cheek.

Next time, in a railway carriage on their way to Kew Gardens, she praises him for the beautiful tact he showed before, giving her but a brother’s kiss at such a moment. He takes the praise. He says: He was exalted above the senses. (Though truth is, he doesn’t know any other way of kissing.)

She says: nothing. She just leans in to kiss him properly, opening his mouth with a gentle, probing tongue.

He is greatly startled. He says: They must move carefully. Perhaps she ought to seek a legal separation instead of a divorce. Would that spare her social ostracism and financial ruin? Perhaps they ought to wait until her mother has died? It is so hard to know what to do.

She says: She is tired of these public meetings in the reading room and the railways, the parks and galleries. Shouldn’t she come round to his new flat next time?

He says to himself, Olivia is like a mild heroine of his plays, she seems a part of himself, she is so friendly and unexacting, she will understand him and demand nothing that he cannot give.

To her he says: that is what he looks forward to having. When the time is right, if her husband agrees, perhaps when the child is grown.

Olivia says, she asked her husband for separation, but he became so distressed. It may be kinder to de- ceive him.

She says: Now that WB has his own flat, there is nothing to stop them.

She says: They will need a double bed. She will go with him to buy it.

She says: Healy’s Furniture Emporium. Tottenham Court Road. Next Tuesday afternoon.

They buy the bed, to WB’s embarrassment and anx- iety about the expense added by each additional inch. She sets a date and arrives promptly and waits in the front room, patiently smoking as he fusses about. He is imagining the taste of the tip of her tongue, the smoky scent of her hair unbound and unwound. He is doing so much imagining that when they finally make it to the bedroom, and a sufficient state of undress, he has fomented himself into a great nervous excitement that renders him impotent.

His horror of horrors is realized.

He can never see her again. The embarrassment would be excruciating. Disabling.

Yet he knows he will see her again, the very next day, at the Reading Room where they are researching the work of Nicholas Flamell.

Sitting in his library seat the following morning (he had to force himself not to stay at home), he trembles with shame as he sees her approach, dreading her coldness, anticipating her rejection. He can live with her disdain so long as she does not share it around, tell Johnson or any other of their mutual friends.

What Olivia does is greet him with just the same light kindness as always, and fall into conversation as open and free as ever. So, a week later, they try again, and though once again he suffers a paroxysm of pain and nervousness, after another round of tea and talk, finally, almost two years after the The Yellow Book inaugural dinner where the thought first crossed his mind, by the womanly virtues of kindness and patience, WB’s maiden voyage is launched.

More here

‘I see,’ said Michael Robartes, ‘that you are still fond of incense, and I can show you an incense more precious than any you have ever seen,’ and as he spoke he took the censer out of my hand and put the amulets in a little heap between the _athanor_ and the _alembic_.

I sat down, and he sat down at the side of the fire, and sat there for awhile looking into the fire, and holding the censer in his hand. ‘I have come to ask you something,’ he said, ‘and the incense will fill the room, and our thoughts, with its sweet odour while we are talking. I got it from an old man in Syria, who said it was made from flowers, of one kind with the flowers that laid their heavy purple petals upon the hands and upon the hair and upon the feet of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, and folded Him in their heavy breath, until he cried against the cross and his destiny.’

He shook some dust into the censer out of a small silk bag, and set the censer upon the floor and lit the dust which sent up a blue stream of smoke, that spread out over the ceiling, and flowed downwards again until it was like Milton’s banyan tree. It filled me, as incense often does, with a faint sleepiness, so that I started when he said, ‘I have come to ask you that question which I asked you in Paris, and which you left Paris rather than answer.’

He had turned his eyes towards me, and I saw them glitter in the firelight, and through the incense, as I replied: ‘You mean, will I become an initiate of your Order of the Alchemical Rose? I would not consent in Paris, when I was full of unsatisfied desire, and now that I have at last fashioned my life according to my desire, am I likely to consent?’

‘You have changed greatly since then,’ he answered. ‘I have read your books, and now I see you among all these images, and I understand you better than you do yourself, for I have been with many and many dreamers at the same cross-ways. You have shut away the world and gathered the gods about you, and if you do not throw yourself at their feet, you will be always full of lassitude, and of wavering purpose, for a man must forget he is miserable in the bustle and noise of the multitude in this world and in time; or seek a mystical union with the multitude who govern this world and time.’ And then he murmured something I could not hear, and as though to someone I could not see.

For a moment the room appeared to darken, as it used to do when he was about to perform some singular experiment, and in the darkness the peacocks upon the doors seemed to glow with a more intense colour… He leaned forward and began speaking with a slightly rhythmical intonation, and as he spoke I had to struggle again with the shadow, as of some older night than the night of the sun, which began to dim the light of the candles and to blot out the little gleams upon the corner of picture- frames and on the bronze divinities, and to turn the blue of the incense to a heavy purple; while it left the peacocks to glimmer and glow as though each separate colour were a living spirit. I had fallen into a profound dream-like reverie in which I heard him speaking as at a distance. ‘And yet there is no one who communes with only one god,’ he was saying, ‘and the more a man lives in imagination and in a refined understanding, the more gods does he meet with and talk with…The many think humanity made these divinities, and that it can unmake them again; but we who have seen them pass in rattling harness, and in soft robes, and heard them speak with articulate voices while we lay in deathlike trance, know that they are always making and unmaking humanity, which is indeed but the trembling of their lips.’

He had stood up and begun to walk to and fro, and had become in my waking dream a shuttle weaving an immense purple web whose folds had begun to fill the room. The room seemed to have become inexplicably silent, as though all but the web and the weaving were at an end in the world. ‘They have come to us; they have come to us,’ the voice began again; ‘all that have ever been in your reverie, all that you have met with in books…

I made a violent effort which seemed almost to tear me in two, and said with forced determination: ‘‘I command you to leave me at once, for your ideas and phantasies are but the illusions that creep like maggots into civilizations when they begin to decline, and into minds when they begin to decay.’ Seizing the _alembic_ from the table, was about to rise and strike him with it, when the peacocks on the door behind him appeared to grow immense; and then the _alembic_ fell from my fingers and I was drowned in a tide of green and blue and bronze feathers, and as I struggled hopelessly I heard a distant voice saying: ‘Our master Avicenna has written that all life proceeds out of corruption.’

The glittering feathers had now covered me completely, and I knew that I had struggled for hundreds of years, and was conquered at last. I was sinking into the depth when the green and blue and bronze that seemed to fill the world became a sea of flame and swept me away, and as I was swirled along I heard a voice over my head cry, ‘The mirror is broken in two pieces,’ and another voice answer, ‘The mirror is broken in four pieces,’ and a more distant voice cry with an exultant cry, ‘The mirror is broken into numberless pieces’; and then a multitude of pale hands were reaching towards me, and strange gentle faces bending above me, and half wailing and half caressing voices uttering words that were forgotten the moment they were spoken.

I was being lifted out of the tide of flame, and felt my memories, my hopes, my thoughts, my will, everything I held to be myself, melting away; then I seemed to rise through numberless companies of beings who were, I understood, in some way more certain than thought, each wrapped in his eternal moment… All things that had ever lived seemed to come and dwell in my heart, and I in theirs; and I had never again known mortality or tears, had I not suddenly fallen from the certainty of vision into the uncertainty of dream, and become a drop of molten gold falling with immense rapidity, through a night elaborate with stars, and all about me a melancholy exultant wailing. I fell and fell and fell, and then the wailing was but the wailing of the wind in the chimney, and I awoke to find myself leaning upon the table and supporting my head with my hands.

I saw the _alembic_ swaying from side to side in the distant corner it had rolled to, and Michael Robartes watching me and waiting. ‘I will go wherever you will,’ I said, ‘and do whatever you bid me, for I have been with eternal things.’

More here