So it felt timely to re-release a centenary edition of the first two volumes of this Irish trilogy in advance of publishing the third and final book of this story.

Isabel Allende once said, ‘Write what should not be forgotten’. That’s my guiding principle as a writer.

I grew up in a village in the south-eastern corner of Ireland, called Murrintown. Back then it was tiny—no more than a handful of houses, a church, a post office, and our shop and pub—but small as it was, an unspoken divide separated its few families.

As children, we knew who was one of ‘us’. Nobody put into words who or what ‘we’ were, but we carried the divide within us. We were born it and we passed it on, all without knowing why. As I grew into my teens, I began to wonder why.

I discovered that the divide centered around whether a family voted for Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael, the two organizations have dominated party politics in the Republic of Ireland since the foundation of the state. Yet the more I learned about them, the more these opponents looked the same. Both patriarchal, both pietistically Roman Catholic, both right of centre. Both ignoring most of what I—a young, left-leaning, progressive woman—thought important.

Their division could be traced back to an event called the Irish Civil War that had happened fifty years before. I had heard whispers of this war but been taught nothing about it. Our school history books were full of our glorious Easter 1916 Rising against British rule, of the glorious War of Independence of 1918 to ’21, of our glorious admission into the League of Nations in 1924. But the Civil War of 1922/23? That was a blank page. And, as my father’s uncle had been killed in that war, murdered the whispers under the blank page alleged, that was the one I wanted to know more about.

Was it true that he’d been shot dead by his best friend, a ‘Free Stater’ who’d supported the (partial) independence treaty with Britain? That he’d been killed because he was what Staters called an ‘Irregular’, opposed to the treaty? That he and others in my family had fought on after the independence war was over, trying to destabilise the fledgling state?

His sister, my great-aunt Agnes, lived with us. Passionately republican and passionately Fianna Fáil—her proudest boast was that De Valera once slept in our house—she evaded all my questions but she did show me two pictures. One of her in uniform, holding up the badge that said she had been a member of Cumann na mBan, the women’s auxiliary unit that had also fought against the British, and after the peace talks, against the treaty. And one of her dead brother. Yes, he’d been shot in the Civil War.

But why?

No answer. The pictures were silently returned, with a tragic air, into their yellowing envelope, and solemnly replaced in her dressing-table drawer.

I turned to my parents. How could this have happened? How could two men who'd been close friends growing up, comrades in the War of Independence of 1921, have become murderous enemies a year later? And what part had my Auntie Ag played in it all? My persistent questions went unanswered. Nobody knew anything. Least said, soonest mended. Whatever you say, say nothing.

Some day, I told my friend who sat beside me in school, I was going to write a book about all this. Then I grew up, and rejected it all—the public, nationalist politics and the private family history. I left home, went to university, found feminism and a different way of thinking about everything.

Some day, I told my friend who sat beside me in school, I was going to write a book about all this. Then I grew up, and rejected it all—the public, nationalist politics and the private family history. I left home, went to university, found feminism and a different way of thinking about everything.

When you reject something, though, you're not indifferent—as I learned when, approaching middle-age, I set about fulfilling that long-ago vow to my friend, and beginning that long-promised book. By then I’d been working as a features journalist for a decade, so I began to interview people who’d been alive in that time (Auntie Ag was long dead).

I turned to old County Wexford newspapers, old documents in libraries and archives, old books written by those who’d been part of the conflicts of that time. I began to make notes. And somewhere along the line, research and memory gave way to imagination. I never did find out what really happened to my great-uncle but it ceased to matter. It turned out that I was writing a novel.

The story of another family, the Devereux-Parles, similar-but-different to mine. And another progressive young woman, Jo Devereux, similar-but-different to me, tracing her family history back to a similar-but-different event.

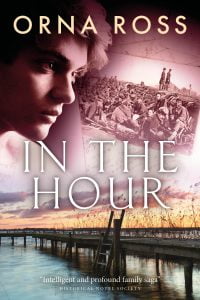

What happened to Jo, her ancestors and descendants, grew into a three-volume saga, After the Rising, Before the Fall and In the Hour, covering the lives of five generations of women, across two continents. Throughout, there are three time frames—ancestor time (1920s to 1950s), past time (1960s to 80s), and present time (1990s to 2020s)—and the story is told by moving backwards and forwards across this one hundred years of modern Irish life, at home and abroad.

As I look back over the writing of this trilogy, I see now why it had to be a novel. Only fiction could recreate those people who’d been wiped out of the history books. I hope they, and their way of life, will live again for you as you read.

And only the inventions of fiction could contain the truths of that time—and its ambivalent legacy. This love story, this family murder mystery, this belated-coming-of-age tale, explores intimate wars of all kinds—but especially the struggle between the urge for freedom and the longing for belonging.

Before the Fall picks up where After the Rising leaves off, another wave in the family history and in the long hot summer of 1995. We now know who killed Barney, Jo’s great-uncle—or we think we do—but who killed the man who killed him?

Before the Fall picks up where After the Rising leaves off, another wave in the family history and in the long hot summer of 1995. We now know who killed Barney, Jo’s great-uncle—or we think we do—but who killed the man who killed him?

The answer plunges Jo back into Rory’s arms and further under the surface story of nationalist politics she’s been bequeathed, into a the far more primal struggle: that between men and women.

For a century the 1920s civil war conflict in Ireland has been known as ‘The War of The Brothers’ but in this book, I wanted to pay tribute to the sisters: the many women who, in the words of Jo’s Granny Peg and my own Auntie Ag, also ‘did their bit’ for the independence struggle. And also the experience of the many women and men who, like Jo, like me and my family, find they cannot live on the island of Ireland, for whatever reason—but are none the less Irish for that.

People emigrate from their home for all kinds of reasons. Jo cannot find love and a decent life within the legacy of what happened in the 1920s. She moves to London then to San Francisco in search of a life she can occupy and lands herself into the heart of the sexual politics—and the AIDs epidemic—of the 1980s.

There she discovers that politics is not just the nationalist struggle she’s rejected, but the encoding of all kinds of power relations. Colonial politics, constitutional politics, diaspora politics, sexual politics, class politics, race politics, gender politics: all rise from the same root. In all cases, denial and suppression leads to destruction. There she also get to grips with another aspect of her inheritance: alcoholism.

Her gender and addiction struggles mirror her ancestors’ national and intra-national struggles.

Jo painstakingly articulates aspects of the female experience which never should be, yet so often are, forgotten. And she comes up against a key question for any progressive person: why does the push for positive, creative change so often disintegrate into negative, destructive conflict. That’s what happened in the Irish Civil War, that’s what’s happening in the TERF and BIPOC and BAME wars that are playing out online today, that’s what’s happening when a sensitive soul gets lost in addiction.

As Jo puts it: “Rebellion has an energy that sweeps people up but what happens after the rising?” Her bid for escape and her getting lost in alcohol are inter-connected, just as the Irish Easter Rising and Civil War were inter-connected. You can't talk about one without the other. You can’t claim the glory of the Rising if you ignore the shame of what followed. You can’t walk away from your past, you must accept it as you work for a finer future.

And so we come to now. How Ireland commemorates those years of 1922 and 1923, and what grew out of them, a hundred years on will be telling. The commemoration of the 1916 Rising has been both praised for being “well organised, sensitive, dignified and inclusive”, and also criticised for the opposite: glorifying a “narrow concept of Irishness.” 1 Which is it? Both, of course. And the only way to prevent conflict around two opposing sides on this is to allow all the other voices to be also heard, so that we see the larger truth beyond the nationalist story.

The Rising was a theatre of insurrection, inspiring the “terrible beauty”2 of violent rebellion for a century, while simultaneously generating pride in a newborn nation. The Civil War was a less complex, but more terrible affair. A kitchen conflict. Far more everyday, far more personal, and far more frightening for that.

The Rising was a theatre of insurrection, inspiring the “terrible beauty”2 of violent rebellion for a century, while simultaneously generating pride in a newborn nation. The Civil War was a less complex, but more terrible affair. A kitchen conflict. Far more everyday, far more personal, and far more frightening for that.

And far more relevant to the Ireland of the 2020s, as Brexit politics energise the prospect of a united Ireland, as advances in women’s and LGBTQ+ rights teach us something about relatively peaceful revolution, as the never-ending movements of emigration and immigration show up our notions of nation.

The question for us in these centenary years is: what might we now imagine into being, as a dispersed and diverse people, scattered across the globe but united by this strange, slippery, scintillating identity, this being Irish? What new ways await us? And what value does our learning, our positive, creative change, have for others? Especially other colonised peoples.

On on hand, the guerrilla war tactics of the Irish independence war inspired other nations like India into similar independence wars, with all their bloody fallout and partial autonomy. More significantly for the themes explored in this trilogy, Ireland was the first colony of what went on to be the age of imperialism’s largest empire.

It was on the island of Ireland that colonisers first practiced the plantations and penal laws that stripped away culture, language and dignity. Refined and surpassed, these tactics went on to be used against other peoples in Africa, the Americas, and beyond, and by other empires.

Such misrule breeds enslavement, famine and yes, civil war. Countries and people devoured and then devouring themselves.

You can draw a direct line between the Tudor plantations of Ireland in the 16th century, through the signs 20th century WASP landlords and ladies in the UK and US used to put in their windows (No dogs, no blacks, no Irish), to the Black Lives Matter protests of today.

Knowing the truth of our past matters: all the truths, not just one narrative. When you do, you can reclaim it, as a London couple, Richy and Taurayne, have done with their thriving business selling T-shirts that proclaim More dogs, more blacks, more Irish.

Knowing the truth of our past matters: all the truths, not just one narrative. When you do, you can reclaim it, as a London couple, Richy and Taurayne, have done with their thriving business selling T-shirts that proclaim More dogs, more blacks, more Irish.

Know your story, the t-shirts say on the back. That’s what I set out to do as I wrote this book and though I didn’t succeed, as Jo does, in finding out whodunnit, I learned what I needed to know.

Facing into those troubled times of a hundred years ago, deciding what—and how—we choose to remember and commemorate the Civil War will show Ireland what it’s made of today, at home and abroad. I offer this story about the people of Mucknamore, this murder mystery that is also a true love story, as my contribution to the multitude of voices, from within and outside the Irish identity, that we need to hear.

It releases some of the secrets and lies that were interred by Ireland in its new, partitioned nation. But don’t expect it to “solve” everything, or to leave no loose ends. That isn’t how it happens after a rising. Or before a fall.

Orna Ross, London, 2020.

1 Dennis Kennedy. 2016. “Pride in ‘inclusive’ 1916 commemoration rings hollow”. Irish Times.

2 WB Yeats. 1921. “Easter 1916”