I'm happy to see that the WB Yeats Bedford Park Project is back in post-pandemic action!

I was a proud supporter of the crowdfunder that raised money to create this public artwork in Bedford Park, West London, where WB Yeats spent some childhood years, and much of his 20s.

Unfortunately, the event we've all been waiting form, the “unveiling” of the centrepiece sculpture commissioned to coincide with Yeats's birthday in June, has had to be postponed, due to delays in material supply.

This artwork, Enwrought Light, is the brainchild of the poet Cahal Dallat, and is being created by internationally acclaimed London artist Conrad Shawcross.

On the plus side, the re-scheduling to Tuesday 6th September, now means the unveiling will be part of the annual Chiswick Book Festival. Full event details to follow.

You can read more about the WB Yeats Bedford Park Project in Dallat's essay on the Irish Literary Society's blog: Opening a Can of Worms.

Stay tuned to find out more and keep an eye on www.wbyeatsbedfordpark.com.

Bedford Park

The WB Yeats Bedford Park Project: Enwrought Light

The sculpture will be positioned at the entrance of Bedford Park, between “the roadway and the pavements grey”, that Yeats would have walked on his way to school and library and engraved in a wide stone base, with Yeats’s words:

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half light

Artists Impression of how the WB Yeats Bedford Park Enwrought Light sculpture will look

These, of course, are lines from the love-poem, He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven.

The poem has long fascinated Conrad as capturing an artist's interest in materials and light, alongside the crafts of the Arts-&-Crafts movement. William Morris and his sister were friends of the Yeats family and Willie Yeats's sister Lily embroidered mediaeval tapestries and costumes for Morris for some years.

The poem also embodies Bedford Park's underlying philosophy of enriching everyday life with beauty, with aesthetic buildings and artefacts.

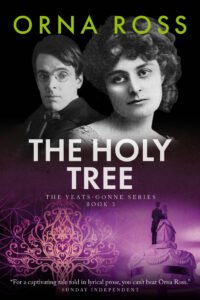

Bedford Park in A Holy Tree

It was, of course, to the family home at Bedford Park that Maud Gonne famously came calling, the event that WB remembered decades later as when, “the troubling of my life began”.

It was, of course, to the family home at Bedford Park that Maud Gonne famously came calling, the event that WB remembered decades later as when, “the troubling of my life began”.

He never wrote a poem about Bedford Park, but then he hardly ever wrote about anywhere in England. One of his biographers claims he made but three specific references to England in his entire output of poetry–and almost none to specific English places.

Here is the scene from The Holy Tree, where Maud Gonne first calls on the Yeats family at Bedford Park.

The carriage jerks to a stop. “No. 3 Blenheim Road, Miss.”

They are here! A quiet thoroughfare, winding and lined with new trees. Attractive, red-brick house with Dutch gables, white casement windows, a porch with decorative tiling. What the architects like to call Queen Anne revival.

Maud Gonne has done her research and read an article in Harper’s Monthly Magazine that praised Bedford Park for its mix of antiquity and progressiveness. The village feel, complete with its Tabard Inn named after Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, offers also co-operative stores, and clubs open to women and men, equally. It was the world's first purpose-built artists' colony, full of interesting people: anti-imperialists, suffragists, vegetarians. No wonder the Yeats family chose to live here.

“You can wait for me,” she says to O’Driscoll. “I shouldn’t be too long.”

She knows she shall be at least an hour, but she would keep the fare running so Mrs. O’Driscoll and the little O’Driscolls, of whom there is doubtless a surfeit, might have a good week. His profuse Irish thanks follow her out of the carriage, through the little gate, and up the pathway.

As she approaches the doorway, she consciously pulls herself up, and arrives at the front door with what she hopes is calm dignity.

Suppressing a shiver, she rings the doorbell with a sense of significance. It’s not just the freezing fog that makes here shiver. She feels as if the bell is ringing down through the future, striking up the poetry that is to come, and the spiritual and political work she and the poet will do together, a kind of poetry too.

So when the serving girl answers the door, she speaks to her slowly, and with a sense of import. “It’s Miss Gonne,” she says, proffering her letter of introduction. “Miss Maud Gonne, lately come from Ireland.”