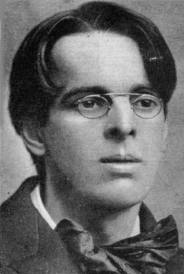

WB Yeats, always known as “Willie” by Maud and Iseult Gonne

Now that the Go Creative! Books are at the editing and formatting phase, I'm back writing fiction again – specifically the books based on the extraordinary triangle at the heart of the love life of the Irish poet WB Yeats.

When I was 13 or 14 I was introduced, as all Irish schoolchildren are, to this poet who towers, literally and figuratively, over Irish writing. The poems we studied at that stage were the early ones,”The Lake Isle Of Inishfree” [see below for copies of all the poems mentioned in this article] and “The Stolen Child”; and “He Wishes For The Cloths Of Heaven”, in which the Yeats portrays himself as a sort of cosmic Sir Walter Raleigh, laying down the light of the heavens under the feet of his beloved, Maud Gonne.

Our teacher, Miss McNamara, read the poems in a slow, mannered style she called Yeatsian, which had laughter simmering in the classroom but I was a very moony teenager, who'd already had her heart broken more than once, and was immediately taken not just with the poetry but with the story of unrequited love.

On 3 August 1891 WBY proposed marriage to Maud Gonne for the first time, but she refused him as she was to do many times again. A British heiress turned Irish revolutionary, independent-minded, auburn-haired, over six feet tall at a time when the average height was inches shorter than it is now, with high bearing, impeccably dressed in the latest Parisian style, Maud broke hearts wherever she went. The journalist RL Steen pronounced her “the most beautiful woman in the world.

Maud Gonne: “I had never thought to see in a living woman such great beauty.”

From her repeated refusals to his proposals WB, or “Willie” as Maud knew him, carved a life-long poetic career.

Never give all the heart, for love

Will hardly seem worth thinking of

To passionate women if it seem

Certain…

… He that made this knows all the cost,

For he gave all his heart and lost. [Never Give All The Heart.]

I have spread my dreams under your feet/tread softly, for you tread on my dreams [He Wishes for The Cloths Of Heaven.]

I couldn't get enough of these poems. I wafted around in a befuddle of burning youths with beating hearts and glimmering girls with pearl-pale hands and apple blossom hair that wound around stars that grew out of the air…

One of the girls brought in a picture of Maud Gonne that her mother had at home, a picture taken around the time Yeats had written of her: “I never thought to see in a living woman such great beauty.” It was a beauty lost on the girls of Loreto convent Wexford in 1973, when the almost-masculine, handsome-rather-than-pretty ideal of the Edwardians was in decline. My classmates picked Maud’s image apart: her face was too broad, her chin too strong, her jaw too set, her forehead too high…

“Maybe she didn’t photograph well,” I suggested. “Maybe you had to be in her presence to get a sense of her.”

Like Yeats, I wanted the woman who inspired such wonderful words to be perfect and I wanted their love to win through.

So imagine my chagrin when, a couple days into our work on Yeats, Miss McNamara casually mentioned that in his later years, the poet had moved his romantic feelings from Maud to her daughter.

“Her daughter?” I cried out into the classroom. “No, he couldn’t have.”

Whereupon everybody laughed, out loud this time.

And so I was launched upon my lifetime interest in Yeats and the Gonnes, Maud and Iseult. And on my own future as a writer of poems and stories.

The interest followed me into senior school, where we were introduced to the later works like “Among Schoolchildren” and “Sailing To Byzantium”, then into university, and then off syllabus, reading books I barely understood other topics I was too young to appreciate: the visions, the occult lore, the interest in Western magic and Celtic spirituality.

It was in a book of essays called Yeats And Women, that I first saw beyond the myths Yeats had created and found my way into the story of what had really happened between him and Maud and Iseult Gonne — and began to research their lives in earnest for a book of my own.

The publication history of that book is a story for another blog post but now, I'll publish a new edition next year in the form of a trilogy. The first The Secret Rose tells the story of Maud & Willie between their meeting in 1889, when he said, “the troubling of my life began” to the fateful moment in 1898, when she first shared with him the secrets of the heart of her life.

A Child, Dancing tells the story of Willy and Iseult between the years of 1908 and 1918, when he proposed marriage to her when she was 23 and he was 50. and the final book, But A Dream, tells the mother and daughter story of Iseult and Maud from 1919 to the end of the Irish Civil War in 1923, and the end of their close connection with Willie for many years.

The story is told as fiction but it's historically as accurate as I could make it. Most of the dialogue has its roots in a real document: a letter, a poem, a diary entry. The research took me from Dublin to New York, and down the byways of such topics as the Western tradition of magic, automatic writing, what it means to be a mentor, and many other themes. At heart, it's a story about love; not romantic love but the kind of spiritual love described by Emily Dickinson as “anterior to life, posterior to death, initial of creation and the exponent of breath.”

Yeats called it the search for perfection and he devoted his life to it.

This week, I'll be blogging something about these three fascinating people every day. I hope you'll enjoy finding out more about them — and if you have any stories or interest yourself, I'd love to hear about that.